In modern output systems, not every printing task relies on ink. Certain environments demand instant results, consistent repetition, and minimal mechanical complexity. From this need, thermal printing developed as a heat-based printing approach where output is formed through controlled temperature, giving rise to devices like the thermal printer, built specifically for speed and operational consistency.

The idea itself is deceptively simple. Instead of depositing ink onto a surface, thermal printing relies on heat to trigger a reaction, either within specially coated paper or through a transfer layer that releases pigment under precise temperatures. In this model, the thermal printer functions as an activator rather than a delivery system.

This inkless printing model reduces variables that often complicate traditional systems: drying time, nozzle clogging, toner residue, and alignment drift. In operational settings where output is repetitive and time-sensitive, those variables matter more than resolution nuance or color depth.

The persistence of this technology is not accidental. Thermal printing thrives because it aligns closely with transactional workflows—receipts, labels, tickets—where speed and uniformity outweigh permanence. In these contexts, this printers type is selected not for versatility, but for reliability under repetition.

A thermal printer does not attempt to be universal; it is optimized for narrow, high-frequency tasks where failure or delay carries immediate cost. That specialization has allowed the technology to remain relevant even as broader printing ecosystems evolve.

Industry-scale adoption reinforces this position. According to research by Grand View Research, thermal printing technologies accounted for a global market value of approximately USD 49.3 billion in 2024. This figure does not signal consumer preference so much as infrastructural reliance—evidence of how deeply heat-based printing is embedded in everyday transactional and labeling systems worldwide.

Within modern output environments, the thermal printer functions less as a general-purpose device and more as a purpose-built instrument. Its role is defined by predictability: predictable output time, predictable maintenance behavior, and predictable performance under controlled conditions. That clarity of intent explains both the technology’s longevity and the boundaries it continues to respect.

Thermal Printer Definition

A definition of a thermal printer only becomes meaningful when it is framed by consequences rather than terminology. This technology is not defined by what it contains, but by what it deliberately removes.

There is no ink reservoir to refill, no toner to fuse, and no liquid medium to manage. Instead, the entire printing outcome depends on how heat is generated, controlled, and transferred to a receptive surface. That single design decision reshapes everything else: speed, maintenance behavior, output lifespan, and usage context at the device level.

In contrast, inkjet and laser systems treat printing as a process of material deposition. Inkjet printer devices propel microscopic droplets onto paper, relying on absorption and drying. Laser printers bind powdered toner to a surface using heat after electrostatic placement.

Both approaches depend on consumables that exist independently of the paper itself. Thermal printing technology collapses that separation. In a thermal printer, the print mechanism and the medium are inseparable, because the paper or ribbon must actively respond to heat in order for any image to appear.

This tight coupling between heat, media, and output is what fundamentally differentiates a thermal printer from other printer classes. The device does not “apply” content onto a surface; it activates a reaction already embedded within the material.

When heat-sensitive paper passes beneath the print head, localized temperature changes trigger chemical transformations that darken specific areas. Text, barcodes, and images emerge without any substance being transferred onto the page. The absence of ink or toner is not a convenience feature—it is the structural core of how a thermal printer operates.

That design also explains why thermal printers tend to occupy narrower functional roles. They excel where consistency, repetition, and mechanical simplicity are more valuable than visual richness or long-term archival quality.

Because the output depends on controlled heat exposure, the system rewards precision over flexibility. The same principle that enables rapid, uniform printing also imposes clear boundaries on durability and media choice.

Heat as the Core Printing Mechanism

At the center of this process sits the print head, a dense array of microscopic heating elements aligned across the width of the paper path. Each element can be activated independently, reaching specific temperatures in fractions of a second.

When energized, these elements apply heat directly to the passing medium, forming dots that collectively become characters, symbols, or images. There is no intermediary step; the print head and the media interact directly within the thermal printer itself.

Because heat replaces ink, the printing surface must be engineered to respond predictably. In direct thermal systems, heat-sensitive paper contains a coating that reacts to temperature changes by darkening. In thermal transfer systems, heat melts ink from a ribbon and transfers it onto a separate substrate. In both cases, heat is not incidental—it is the sole driver of image formation.

This reliance on thermal activation removes many failure points common in other printing technologies. There are no clogged nozzles, no toner alignment issues, and no drying delays. At the same time, it introduces a different dependency: temperature control must be precise.

Too little heat produces faint output; too much can blur edges or degrade the media. The apparent simplicity of a thermal printer hides a high demand for thermal accuracy.

How Thermal Printers Works

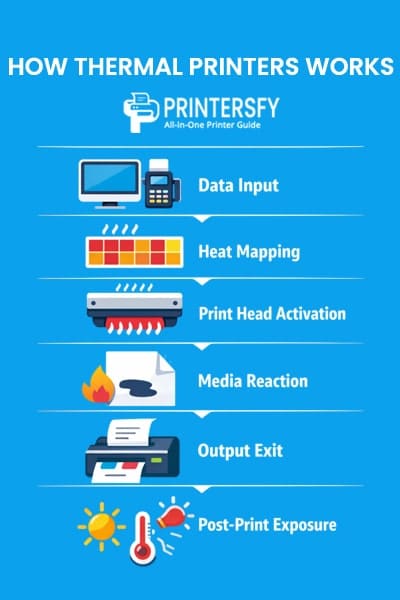

The printing process begins digitally, like any other system, with data sent from a host device. What follows, however, diverges sharply from ink-based workflows. Instead of translating data into fluid movement or electrostatic patterns, a thermal printer converts information into a heat map. Each pixel of the intended output corresponds to a heating instruction—how hot, how long, and where.

As paper advances through the printer, driven by rollers and guided along a fixed path, it passes directly beneath the thermal print head. The printer synchronizes paper movement with heat activation so that each heating element contacts the correct position at precisely the right moment.

This coordination between motion and temperature defines the printing process. There is no secondary pass, no curing stage, and no waiting period. The output emerges fully formed the moment it exits the device.

Material interaction plays an equal role. Thermal coating paper is engineered with layers that respond rapidly to heat while remaining stable under normal handling conditions. When exposed to the print head’s heat pattern, the coating undergoes a localized chemical reaction, producing visible marks.

The clarity of the result depends on uniform paper quality, stable ambient conditions, and consistent pressure between the head and the media.

Stage System Action Material Interaction Output Implication Data Input Digital print data is received and translated into a heat pattern No physical material involved at this stage Output definition exists as thermal instructions, not ink placement Heat Mapping Printer converts content into localized temperature commands Thermal thresholds are predefined by media characteristics Image precision depends on accurate heat control Print Head Activation Heating elements activate selectively as paper advances Direct contact between print head and thermal surface Immediate image formation without intermediate steps Media Reaction Heat triggers chemical response in thermal paper coating Color change occurs only at heated points Text and graphics appear instantly Output Exit Printed media exits fully formed No drying or curing required Speed and consistency achieved, durability not yet tested Post-Print Exposure Printed surface encounters environment (light, heat, friction) Chemical image remains reactive over time Long-term stability becomes context-dependent

The Role of the Thermal Print Head

The thermal print head functions as both the brain and the muscle of the system. Its structure consists of tightly packed resistive elements, each capable of rapid heating and cooling.

Modern designs emphasize durability and uniform heat distribution, allowing high-speed printing without sacrificing legibility. Because every printed dot is created by direct contact, wear resistance and surface smoothness are critical engineering concerns.

Precision is what allows thermal printers to maintain speed without losing consistency. Heating elements must activate and deactivate thousands of times per second while maintaining exact temperature thresholds. This precision is what enables sharp barcodes and readable text even at high throughput volumes.

Interaction Between Heat and Thermal Paper

Thermal paper is not passive. Its surface contains chemical layers designed to darken when exposed to heat above a specific threshold. The response must be fast, predictable, and localized. If the reaction spreads or lingers, image clarity suffers. This is why paper quality directly affects output consistency and longevity.

Why Image Formation Is Immediate but Fragile

The same immediacy that makes thermal printing efficient also introduces vulnerability. Because images are formed through chemical reactions rather than physical deposition, they remain sensitive to environmental factors.

Excess heat, prolonged light exposure, or friction can continue to influence the printed areas long after printing is complete. Speed and simplicity are gained, but durability becomes a negotiated trade-off—one that defines where thermal printing performs best and where its limitations begin to surface.

Types of Thermal Printing Technology

Although thermal printing is often discussed as a single category, its implementation splits into two fundamentally different technologies. Both rely on heat as the triggering force, yet they diverge sharply in how that heat is translated into a visible result.

The distinction is not cosmetic or product-driven; it is rooted in how each system treats media, durability, and operational control. For any environment using a thermal printer, this distinction shapes not only output quality, but also workflow expectations.

At a structural level, the difference comes down to whether heat activates a reaction inside the paper itself or acts as a transfer mechanism for pigment. That decision determines how permanent the output can be, how flexible the media selection becomes, and how much operational complexity the device tolerates.

Direct Thermal Printing

Direct thermal printing removes all intermediary materials between the print head and the paper. No ribbon is involved. Instead, the printer applies heat directly onto heat-sensitive paper, causing a chemical reaction within the coating that produces visible marks. In this configuration, the thermal printer and the media are tightly bound; one cannot function meaningfully without the other.

This ribbonless printing approach dramatically simplifies the mechanical design. Fewer components mean fewer alignment issues, fewer consumables to manage, and a lower likelihood of mechanical failure.

As a result, a thermal printer configured for direct thermal operation tends to deliver highly consistent output with minimal intervention. Startup time is short, printing is quiet, and maintenance routines are reduced to basic cleaning and paper replacement.

However, this simplicity is not free. Because the image is formed entirely within the paper’s coating, durability becomes conditional. The printed result remains chemically active long after it exits the printer.

Exposure to heat, light, or friction can continue to influence the image, sometimes causing fading, darkening, or loss of contrast. Direct thermal printing therefore aligns best with output that is meant to be read quickly, handled briefly, and then discarded or replaced.

This is why the technology persists in receipts, temporary labels, tickets, and queue systems. In these scenarios, longevity is irrelevant compared to speed, reliability, and cost control. The design does not fail at permanence; it simply never aims for it.

Thermal Transfer Printing

Thermal transfer printing takes a more layered approach. Instead of relying on heat-sensitive paper, it introduces a ribbon coated with ink or resin. When heat is applied, the ribbon melts locally and transfers pigment onto the media beneath it. Heat still drives the process, but the visible image is no longer a chemical reaction within the paper—it is a physical deposit.

This shift changes everything. Because the printed image exists as a bonded layer on the surface, it becomes far more resistant to environmental exposure. Light, moderate heat, and friction have less impact on legibility.

The output can survive longer storage periods, transportation cycles, and handling without significant degradation. In this configuration, a thermal printer becomes suitable for labels that must remain readable across weeks, months, or even years.

The cost of this durability is operational complexity. Ribbons introduce another consumable that must be matched to the media, replaced at intervals, and aligned correctly. Maintenance is no longer minimal, but it remains predictable. Thermal transfer printing accepts this trade-off deliberately, prioritizing output stability over mechanical simplicity.

Where direct thermal printing optimizes for immediacy, thermal transfer printing optimizes for control. The choice between the two is less about preference and more about how much uncertainty a workflow can tolerate after printing is complete.

Direct Thermal vs Thermal Transfer Printing

| Aspect | Direct Thermal | Thermal Transfer |

|---|---|---|

| Printing Medium | Heat-sensitive paper | Ribbon + standard media |

| Print Durability | Lower | Higher |

| Maintenance | Very low | Moderate |

| Typical Use Context | Receipts, short-term labels | Shipping, long-term labels |

Printing Media and Material Constraints

Thermal printing does not treat media as a neutral surface. The paper is an active component of the system, and its physical properties define the boundaries of what the technology can realistically deliver. For any thermal printer, media selection is inseparable from output behavior.

Thermal paper, whether supplied as individual sheets or continuous rolls, is engineered with coatings designed to react within a narrow temperature window. This sensitivity allows rapid image formation, but it also means the output remains vulnerable to environmental influence. Heat, light, and time do not merely affect the print after the fact—they continue the process in subtle ways.

Thermal Paper Composition and Sensitivity

Thermal paper typically contains multiple chemical layers, including a dye and a developer that remain inactive under normal conditions. When exposed to sufficient heat, these components react and darken, forming text or images. The reaction is fast, localized, and requires no added material. That efficiency is why thermal printing achieves such high throughput.

The same chemistry, however, does not become inert once printing is complete. Elevated ambient temperatures, prolonged sunlight exposure, or even sustained pressure can partially re-activate the coating. In uncontrolled environments, this can lead to background discoloration or loss of contrast. Heat sensitivity, in this sense, is not a defect—it is the defining characteristic of the medium.

Receipt paper and thermal paper rolls are optimized for speed and consistency, not permanence. Their performance assumes controlled storage conditions and limited handling. Once those assumptions break, output stability becomes unpredictable.

Longevity and Fading Over Time

Because thermal images are chemically formed rather than physically deposited, their lifespan is conditional. Over time, environmental exposure compounds. Light can bleach contrast, heat can darken backgrounds, and friction can abrade sensitive layers. Archival storage and long-term documentation sit outside the natural strengths of thermal printing.

These limitations do not imply poor engineering. They reflect a design optimized for transactional accuracy rather than historical preservation. A thermal printer delivers certainty at the moment of printing, not guarantees decades later.

Advantages of Thermal Printing in Controlled Environments

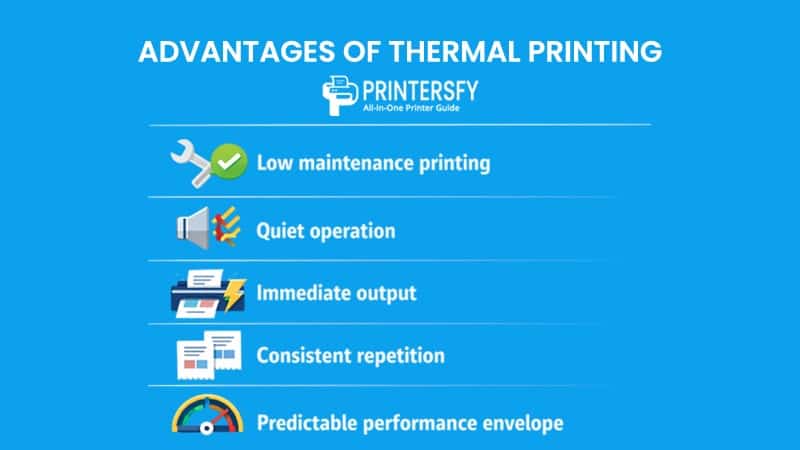

The operational strengths of thermal systems do not emerge from added sophistication, but from deliberate restraint. By stripping away ink delivery paths, complex calibration routines, and post-print curing stages, thermal printing reduces the number of components that can drift, clog, or misalign. In environments where temperature, handling, and workflow remain predictable, this simplicity turns into measurable operational stability.

A thermal printer benefits directly from its minimal mechanical footprint. The absence of liquid ink or powdered toner removes entire categories of maintenance behavior. There are no drying cycles, no residue buildup, and no consumables whose performance degrades unevenly over time. What remains is a system whose reliability depends largely on consistent heat output and media quality.

Key operational advantages in controlled settings include:

- Low maintenance printing: With fewer moving parts and no ink-based subsystems, routine intervention is limited. Maintenance focuses on basic cleaning and media replacement rather than calibration or consumable recovery.

- Quiet operation: Thermal mechanisms generate minimal acoustic output. Without motors dedicated to ink agitation or toner fusion, printers can operate continuously in close-proximity environments without contributing to background noise fatigue.

- Immediate output: Image formation occurs at the moment heat is applied. There is no waiting period for drying, bonding, or curing, allowing printed material to exit the device fully usable.

- Consistent repetition: Output quality remains uniform across repeated jobs because each print cycle follows the same heat thresholds and media response. Variability is reduced as long as environmental conditions remain stable.

- Predictable performance envelope: A thermal printer behaves consistently within defined limits. When paper type, temperature, and handling are controlled, output characteristics remain tightly bounded and easy to anticipate.

These advantages are not universally applicable, nor are they intended to be. They become meaningful precisely because they depend on controlled environments. Within those boundaries, the design philosophy behind thermal printing favors certainty over flexibility, and operational calm over feature breadth.

Limitations and Trade-Offs of Thermal Printing

The strengths of thermal systems are inseparable from their constraints. What simplifies operation also narrows flexibility, particularly in how output ages and how it reacts to its surroundings. These limitations are not design oversights; they are trade-offs embedded in the physics of heat-based image formation.

Print durability remains the most visible boundary. Because images are created through chemical reactions or heat-driven transfer, they retain a degree of sensitivity after printing. According to a technology outlook report by Credence Research, while thermal printing is widely adopted for its inkless operation and low mechanical complexity, long-term output durability is constrained by the heat-sensitive nature of thermal paper. This observation reflects a systemic reality rather than a media flaw.

A thermal printer delivers certainty at the point of output, not permanence over time. In environments where printed information must remain legible for extended periods without controlled storage, this limitation becomes operationally significant.

Environmental Sensitivity

Heat, light, and friction continue to interact with printed surfaces long after the job is complete. Elevated temperatures can darken backgrounds, prolonged light exposure can reduce contrast, and physical abrasion can disturb chemically formed images. These effects accumulate gradually, making degradation less predictable than in pigment-based systems.

Output Constraints

Color reproduction is inherently limited. Most thermal systems operate in monochrome, and even thermal transfer configurations rely on discrete ribbon choices rather than fluid color mixing. Resolution, while sufficient for text and barcodes, is optimized for clarity over detail. A thermal printer favors functional readability, not visual nuance, and that preference defines its output ceiling.

These constraints do not invalidate the technology. They simply define where it should—and should not—be applied.

Typical Use Cases Shaped by Thermal Technology

Thermal systems are chosen not because they outperform all alternatives, but because they align precisely with certain operational demands. Receipt printing, label printing, and logistics labeling share a common requirement: information must appear instantly, repeat consistently, and remain readable for a defined window of time.

In transactional contexts, output is consumed immediately. Receipts are verified, tickets are scanned, and labels guide short-term movement rather than archival reference. In these workflows, a thermal printer fits naturally because its speed and consistency outweigh concerns about long-term durability.

Logistics environments extend this logic. Labels must survive handling, scanning, and transport, but not necessarily years of storage. When paired with appropriate media, thermal systems meet that requirement efficiently. The technology is selected not for versatility, but for fit—an alignment between design intent and operational reality.

Where permanence, color fidelity, or archival stability become priorities, thermal printing steps aside. Where immediacy, predictability, and controlled conditions dominate, it remains difficult to replace.

When Thermal Printing Is Not the Right Choice

Thermal systems are designed around immediacy and control. When those assumptions no longer hold, their advantages begin to erode into practical constraints. A thermal printer becomes a poor fit once printed output is expected to endure handling, storage, or environmental variation beyond a short operational window.

The first pressure point appears in long-term documentation. Heat-based image formation relies on chemical reactions or heat-driven transfer, both of which remain environmentally reactive over time. Archival printing requires output stability measured in months or years, often under inconsistent lighting and temperature conditions. In such contexts, a thermal printer exchanges short-term reliability for long-term unpredictability, making it unsuitable for records, contracts, or compliance-driven documents.

Several conditions consistently push thermal printing beyond its natural limits:

- Long-term document storage: Printed content may fade, darken, or lose contrast over time, particularly when exposed to light or residual heat.

- Archival printing requirements: Workflows that depend on permanent legibility conflict with the chemically reactive nature of thermal media.

- Uncontrolled storage environments: Variations in temperature, pressure, or humidity can continue to influence printed output long after printing is complete.

Material behavior reinforces these boundaries. Thermal media is engineered for responsiveness, not endurance. Exposure to heat, light, or friction gradually alters the printed surface, turning ordinary storage into a risk factor. Even under careful handling, output from a thermal printer cannot deliver the permanence expected in archival workflows.

Visual limitations further narrow applicability:

- Limited color capability: Most thermal systems operate in monochrome, restricting visual differentiation.

- Contextual resolution ceiling: While text and barcodes remain clear, detailed graphics and nuanced imagery fall outside the technology’s strengths.

In these scenarios, selecting a thermal printer represents a compromise rather than an optimization. The technology does not fail; it simply operates beyond its intended purpose. Recognizing this boundary prevents workflows from relying on a system built for immediacy when longevity is the true requirement.

Where Thermal Printers Fit Among Specialized Printing Systems

Thermal devices occupy a defined position within the broader landscape of specialized printers types. A thermal printer is not designed to replace general-purpose machines, but to serve a narrow functional role where speed and predictability outweigh versatility. Understanding this placement requires grouping printers by function rather than by product category.

Transactional printing forms the first group. Receipt printer systems and label printers focus on rapid, repeatable output tied directly to point-of-sale and operational workflows. Here, a thermal printer excels by producing immediate results with minimal interruption, aligning closely with the tempo of transactions.

Format-oriented systems form another group. Large format printers (plotters), banner printer setups, A2 printer and A3 printer platforms prioritize scale and layout flexibility. Their value lies in accommodating size variation and visual planning—requirements that sit far outside the design scope of thermal systems.

A third group centers on image and material behavior. Photo printer devices emphasize color depth and tonal accuracy, while flex printer and textile printer systems manage specialized substrates and inks. These machines trade speed for surface control and visual richness.

Within this structure, a thermal printer stands apart as a specialized printer built for narrow efficiency. It operates quickly, within tight physical limits, and with a clear functional intent. That focus is not a limitation in itself; it is the reason the technology remains indispensable where precision timing and consistency matter more than breadth.

Conclusion

Thermal printing persists not because it tries to compete with every other printing method, but because it never attempts to. Its value comes from clarity of intent. A thermal printer is designed to perform a narrow set of tasks with speed, consistency, and minimal operational friction, and it does so by accepting clear boundaries around durability, media choice, and visual flexibility.

Seen through this lens, thermal printing is best understood as a specialized printing technology rather than a general-purpose solution. It favors functional printing systems where output is transactional, repetitive, and immediately actionable. The technology aligns heat, media, and motion into a tightly controlled process that minimizes variables at the moment of printing, even if it concedes longevity afterward.

Those concessions are not weaknesses in isolation. They are the reason thermal systems remain stable in environments where predictability matters more than permanence. A thermal printer fits cleanly into workflows that value instant legibility, low maintenance behavior, and consistent repetition under controlled conditions. Outside those parameters, its relevance fades—not because it underperforms, but because it was never designed to serve those needs.

Understanding thermal printing means recognizing both its fit and its limits. It is a tool shaped by context, not versatility. When used within its intended scope, a thermal printer delivers exactly what it promises: fast, reliable output with minimal complexity. When pushed beyond that scope, the technology signals its boundaries clearly. That honesty of design is what allows thermal printing to remain indispensable in the roles it was built to serve.

FAQs About Thermal Printer

What can a thermal printer be used for?

A thermal printer is commonly used for receipts, tickets, shipping labels, and short-term identification labels where output must appear instantly and consistently.

Can I use normal A4 paper in a thermal printer?

No. Thermal printers require heat-sensitive paper or compatible transfer media. Standard A4 paper does not react to heat and will produce no image.

What is the difference between a thermal printer and a regular printer?

Thermal printers use heat to form images, while regular printers typically rely on ink or toner deposited onto paper.

What happens if you put regular paper in a thermal printer?

The printers will run, but no text or image will appear because the paper lacks a heat-reactive coating.

What are common thermal printer problems?

Common issues include faded output due to paper quality, sensitivity to heat or light exposure, and wear on the print head over time.