Printing on fabric introduces constraints that paper-based systems never encounter, and this is where the role of a textile printer becomes relevant. Unlike sheets of paper that remain flat and stable, textiles behave as living materials. Fibers shift under tension, absorb ink unevenly, and react to heat in ways that can permanently alter color and texture. These characteristics force printing systems to adapt long before a design ever reaches production.

Document printing assumes uniformity. The substrate is standardized, the surface is predictable, and output quality is largely determined by resolution and color management. Textile printing breaks those assumptions. Fabric thickness varies, weave structures influence ink spread, and moisture content affects fixation. Even slight inconsistencies in material handling can distort patterns or reduce durability after washing. As a result, fabric printing demands a workflow that treats material behavior as a central variable, not a background detail.

Industrial needs accelerated this separation. Apparel production shifted toward shorter runs and frequent design changes. Interior and furnishing sectors began requesting printed textiles tailored to specific textures and dimensions. Promotional and event materials required prints that could fold, stretch, and travel without visible degradation. These demands could not be met by adapting office printers or photographic devices built for coated paper.

This pressure reshaped how textile printing systems were designed. Customization became operational rather than optional. Materials expanded beyond cotton to include blends and synthetics, each requiring different ink chemistry and curing conditions. Fabric printing moved closer to manufacturing logic, where consistency across runs and compatibility with varied substrates mattered more than raw print speed.

Within this environment, the textile printer emerged as a specialized printing category. Its purpose is defined less by output format and more by its ability to control fabric movement, ink behavior, and post-print stabilization. Textile printing today exists as a distinct production discipline, positioned alongside other specialized printers that solve material-specific challenges rather than general document output.

What Is a Textile Printer?

A textile printer is a printing system engineered to apply ink directly onto fabric while accounting for the physical and chemical behavior of textile materials. It is not simply a larger printer adapted for soft surfaces. The entire system is designed around fabric as an active medium that stretches, absorbs, and reacts throughout the printing process.

Media Handling and Workflow Characteristics

Unlike paper-based devices, this type of printers must manage fabric in motion. Materials are typically fed in rolls or secured on flat surfaces, requiring precise tension control to prevent distortion. The workflow extends beyond ink deposition. Pre-treatment, drying, and heat-based fixation are often integrated steps, ensuring that color bonds correctly with fibers and remains stable after repeated use or washing. In a textile printing machine, these stages function as a continuous process rather than separate tasks.

Ink interaction further defines how these systems operate. Textile inks are formulated to penetrate fibers instead of resting on the surface. Their performance depends on fabric composition, weave density, and moisture levels. A fabric printer must therefore deliver ink consistently while compensating for variables that change from one material to another. This interaction between ink, fabric, and heat is central to the system’s design.

Why Textile Printers Are Often Called “Machines”

The term “machine” is commonly used because textile printers operate more like production equipment than office devices. They occupy larger footprints, combine multiple subsystems, and are built for sustained operation. Stability across long runs takes priority over convenience or compact form. This industrial orientation reflects the realities of textile printing, where output consistency is tied to mechanical control as much as digital precision.

When compared with office or photo printers, the differences are structural. Office printers assume flat, uniform media and minimal post-processing. Photo printers optimize color accuracy on controlled surfaces. Printing on fabric machines address a different challenge entirely: managing variability at every stage of production. A textile printer exists not as an extension of traditional printing, but as a purpose-built response to the demands of fabric-based output.

Global Market Context of Textile Printing

The scale of fabric-based production places textile output firmly within global manufacturing networks. Apparel supply chains, interior furnishings, promotional materials, and industrial fabrics all depend on printing systems that can operate consistently across regions and materials. Within this environment, the textile printer functions less as an auxiliary tool and more as a foundational component of production capacity.

Market data reflects this structural importance. According to Grand View Research, the global textile printing market reached a value of USD 25.8 billion in 2024 and is projected to expand to USD 56.7 billion by 2033, growing at a compound annual rate of 9.3 percent. This growth is closely tied to rising demand for customized fabric output and the industry’s gradual move away from rigid, setup-heavy production models. As volumes increase alongside variation, printing systems must absorb complexity without sacrificing repeatability.

Economic relevance also emerges from changes in how production is planned. Traditional workflows were optimized for long runs and limited design variation. That logic weakens when fashion cycles shorten and product differentiation accelerates. In response, manufacturers increasingly rely on a textile printer that can support shorter batches, faster transitions, and material flexibility without excessive setup overhead. The value proposition shifts from sheer throughput to operational responsiveness.

This transition is most visible in the digital textile printing market. Grand View Research reports that this segment reached USD 5.8 billion in 2024 and is expected to grow to USD 11.6 billion by 2030. On-demand production models, reduced inventory risk, and the integration of digital workflows have driven adoption. Digital systems align more closely with contemporary manufacturing economics, where waste reduction and speed to market influence profitability as much as output volume.

The rise of digital methods does not eliminate analog processes, but it reshapes investment priorities. Capacity is increasingly distributed between systems optimized for scale and those designed for flexibility. In this context, a textile printer is evaluated by how effectively it integrates design files, material handling, and finishing stages into a cohesive workflow.

At a global level, the textile printing market continues to evolve toward production environments where adaptability carries measurable economic weight. The sustained expansion of both conventional and digital segments suggests that the textile printer remains central to industrial strategy, positioned at the intersection of manufacturing scale and customization demand.

Textile Printing Market Overview

| Segment | 2024 Value | Forecast |

|---|---|---|

| Textile Printing | USD 25.8 B | USD 56.7 B (2033) |

| Digital Textile Printing | USD 5.8 B | USD 11.6 B (2030) |

How Textile Printers Work

Printing on fabric requires a production logic that differs fundamentally from paper-based output. A textile printer is designed around the idea that material behavior cannot be standardized or ignored. Fabric stretches under tension, absorbs liquid unevenly, and reacts to heat as part of the printing process itself. Every stage of operation is built to manage these variables without interrupting production flow.

Unlike document printing, where media stability is assumed, fabric printing treats movement as a controlled variable. Material is guided through the system under constant tension, ensuring alignment while preventing distortion. This approach explains why a textile printing machine integrates mechanical control as tightly as digital precision. The goal is not only to place ink accurately, but to keep fabric behavior predictable from entry to exit.

Ink delivery adds another layer of complexity. Textile inks are formulated to penetrate fibers rather than sit on a coated surface. Their interaction with fabric depends on weave density, fiber type, and moisture content. Heat then becomes an active agent, fixing color into the material rather than drying ink on top. A textile printer coordinates these interactions as a continuous process rather than isolated steps.

These requirements explain why printing on fabric cannot rely on adapted office technology. The system must anticipate variation rather than correct it after output. This logic underpins how modern textile printing equipment is structured and why workflow design matters as much as print resolution.

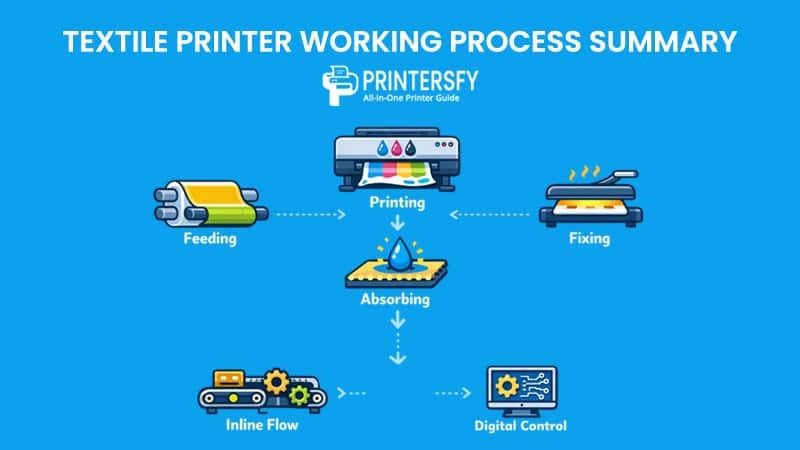

Textile Printer Working Process Summary

| Stage | System Focus | What Happens | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Material Feeding | Fabric handling & tension control | Fabric enters the system as rolls or secured flat media, guided under controlled tension to maintain alignment | Prevents stretching, skewing, and pattern distortion during printing |

| Media Stabilization | Mechanical regulation | Rollers and guides keep fabric movement consistent beneath print heads | Ensures repeatable positioning across long production runs |

| Ink Deposition | Ink–fiber interaction | Textile inks are applied in calibrated volumes, designed to penetrate fibers rather than coat surfaces | Determines color depth, sharpness, and long-term durability |

| Absorption Control | Fabric behavior management | Ink spread is influenced by weave density, fiber type, and moisture content | Prevents bleeding, uneven saturation, and loss of detail |

| Heat Fixation | Chemical bonding | Heat activates the bonding process between ink and textile fibers | Locks color into fabric and stabilizes output for washing and handling |

| Inline Integration | Workflow continuity | Printing, fixation, and stabilization occur in a coordinated sequence | Reduces handling errors and maintains registration accuracy |

| Digital Control (if applicable) | Data-driven adjustment | Design data, ink density, and output parameters are managed dynamically | Supports short runs, customization, and reduced setup time |

Core Printing Mechanisms

At the mechanical level, a textile printer operates as a synchronized system of motion, deposition, and stabilization. Fabric enters the machine either as a roll or a secured flat surface, depending on configuration. Feed rollers and tension controls regulate movement to maintain consistent positioning beneath the print heads. Any deviation at this stage can translate directly into visible distortion.

Ink is applied through precision-controlled print heads calibrated for textile use. In a textile printing machine, these heads are engineered to handle higher ink volumes and different viscosities compared to paper printers. This allows ink to reach fibers evenly without oversaturation. The interaction between ink droplets and fabric surface determines color sharpness, penetration depth, and long-term durability.

Heat and fixation systems follow closely behind ink application. Rather than serving as a simple drying phase, heat activates chemical bonding between ink and fiber. This stage stabilizes color and prepares the fabric for handling, washing, or further finishing. A print on fabric machine often integrates this step inline to prevent misalignment or contamination between stages.

Mechanical stability across these components is critical. The system must maintain consistent conditions over long production runs. This is why a textile printer resembles industrial equipment more than a peripheral device. Its performance depends on balance between mechanical control and chemical interaction rather than speed alone.

Digital Textile Printing Workflow

Digital workflows further reshape how textile printing systems operate. A digital textile printer connects design data directly to production without the need for physical screens or plates. This eliminates setup-intensive stages and allows rapid transitions between designs. The workflow begins with digital file preparation, where color profiles and fabric parameters are aligned before printing starts.

Once production begins, the digital textile printer manages variable data continuously. Designs can change mid-run without stopping the machine, supporting shorter batches and customized output. This capability aligns with modern manufacturing demands, where responsiveness outweighs uniformity. The textile printing machine adapts to these requirements by treating data and material flow as synchronized inputs.

Ink application and fixation remain central, but digital control enhances precision. A digital textile printer adjusts ink density and placement dynamically, compensating for fabric variation in real time. This reduces waste and improves consistency across different materials. The system’s ability to respond to subtle changes is what distinguishes digital workflows from analog methods.

Despite these advances, the underlying principles remain consistent. Fabric behavior, ink chemistry, and heat interaction still define output quality. A print on fabric machine operating digitally must still manage tension, absorption, and fixation with the same rigor as any industrial setup. Digital control refines the process but does not simplify it.

Across configurations, the textile printer functions as a coordinated system rather than a single device. Its workflow reflects the realities of fabric-based production, where every stage influences the final result. Whether operating in analog or digital form, the textile printer succeeds by integrating mechanical precision with material awareness, ensuring that fabric, ink, and heat operate in controlled balance throughout the printing process.

Textile Printing Technologies and Systems

Textile printing technology reflects the diversity of materials, production scales, and operational constraints found across the fabric industry. Unlike document output, where one dominant method satisfies most use cases, textile production relies on multiple technological approaches that coexist rather than replace one another. Each system is shaped by how fabric behaves, how designs are applied, and how results are stabilized for real-world use.

At the center of these systems is the textile printer, whose role is defined less by format and more by process integration. Printing onto fabric requires coordinated control of motion, ink chemistry, and fixation. As a result, textile technologies evolved along two broad paths: analog methods rooted in mechanical repetition, and digital methods built around data-driven flexibility. Both continue to operate in parallel, serving different production realities.

Analog processes developed first, optimized for volume and consistency. They rely on physical tools and repeated setups to achieve uniform results. Digital textile printing emerged later, responding to the need for faster design changes, smaller batch sizes, and reduced setup complexity. These approaches are not competing upgrades but distinct systems shaped by different economic pressures.

Screen Printing vs Digital Textile Printing

Screen printing represents the traditional backbone of textile production. Designs are transferred through physical screens, with each color requiring its own setup. This method excels in long production runs where repetition offsets preparation time. Once configured, output remains highly consistent, making it suitable for standardized designs produced at scale. However, setup complexity limits responsiveness when designs change frequently.

Digital textile printing takes a different approach. Instead of relying on physical screens, designs are transferred directly from digital files to fabric. Digital textile printing reduces preparation time and allows immediate transitions between designs. This capability supports short runs, customization, and on-demand production. The trade-off lies in balancing speed and cost against flexibility rather than maximizing volume alone.

The distinction between these methods shapes how a textile printer is selected and deployed within production environments. Screen-based systems prioritize throughput stability, while digital workflows emphasize adaptability. Neither replaces the other outright. Instead, manufacturers allocate capacity based on order structure, material variation, and turnaround expectations.

Aspect Screen Digital Setup Complex Minimal Customization Limited High Short Runs Inefficient Efficient

Digital Textile Printer Configurations

Within digital environments, system design varies based on how fabric is presented and stabilized during printing. These configurations determine how materials move through the process and how ink interacts with the surface. While underlying principles remain consistent, physical layout influences production efficiency and application range.

A digital textile printer integrates print heads, fabric handling, and fixation into a unified system. The configuration chosen reflects whether fabric remains in continuous motion or is held stationary during printing. This distinction leads to two primary system forms used across modern production lines.

Roll-to-Roll Systems

Roll-to-roll systems feed fabric continuously through the machine under controlled tension. Material enters as a roll, passes beneath print heads, and exits toward drying or fixation stages. This configuration supports higher throughput and consistent alignment across long runs. A fabric printing machine built around roll-to-roll movement prioritizes efficiency and material continuity.

Because fabric remains in motion, tension control becomes critical. Variations in stretch or feed speed can affect registration and pattern accuracy. Roll-to-roll systems are commonly used where production volume and material uniformity justify continuous operation. Their structure aligns closely with industrial manufacturing logic.

Flatbed Textile Printers

Flatbed systems secure fabric on a stationary surface during printing. Material remains fixed while print heads move across it, reducing distortion caused by motion. This configuration accommodates heavier fabrics, textured surfaces, and materials that are difficult to tension evenly. A fabric printer machine using a flatbed design trades speed for stability and control.

Flatbed setups are often selected for specialized applications where precision outweighs throughput. The ability to keep fabric stationary simplifies alignment but limits continuous production. As with roll-based systems, the configuration reflects operational priorities rather than technological superiority.

Across these configurations, the textile printer functions as part of a larger system rather than an isolated device. Mechanical design, ink delivery, and heat fixation operate together, regardless of whether movement comes from fabric or print heads. Digital textile printing enhances control and responsiveness, but it does not eliminate the need for mechanical stability or material awareness.

The broader landscape of textile printing technologies demonstrates that system choice follows production logic. Analog and digital methods coexist because they solve different problems. A textile printer succeeds when its technology aligns with material behavior, workflow demands, and the economic realities of fabric-based manufacturing.

Real Fabric Printing Applications

Real-world fabric printing applications are shaped by production constraints rather than creative ambition alone. What a textile printer is used for depends on how well it manages material variation, ink behavior, and workflow continuity. In practice, applications emerge as consequences of what the technology can handle reliably, not as abstract use cases designed for promotion.

Fabric printing sits at the intersection of design and manufacturing. Unlike paper output, textile surfaces are intended to be worn, washed, stretched, or exposed to environmental stress. This places functional demands on printing systems long after ink is applied. A textile printer becomes valuable when it produces results that survive real use without compromising efficiency at scale.

Across industries, fabric printing applications cluster around four dominant areas. Each reflects a different balance between volume, durability, customization, and material complexity.

Fashion and Apparel

Fashion remains one of the most visible applications of fabric printing, but its requirements are often misunderstood. Apparel production prioritizes consistency across sizes and batches while accommodating frequent design changes. Patterns must align across seams, colors must remain stable after washing, and output must match fabric behavior during wear. These pressures define how a textile printer is deployed in apparel environments.

Shorter fashion cycles and rapid trend shifts favor digital workflows. Fabric printing systems allow brands to test designs in limited runs before committing to larger volumes. Custom textile printing supports seasonal variation and localized collections without forcing long setup times. The ability to switch designs quickly reduces excess inventory and aligns production more closely with demand.

Durability remains central. Printed garments are expected to withstand repeated washing and physical movement. Ink penetration and fixation quality determine whether prints crack, fade, or bleed. In apparel contexts, a textile printer succeeds not through visual impact alone, but through repeatable performance across production cycles.

Home Textiles

Home textiles introduce a different set of constraints. Curtains, upholstery, bedding, and wall fabrics are often larger, heavier, and less uniform than apparel materials. Fabric printing in this category emphasizes scale, pattern continuity, and long-term color stability rather than rapid turnover.

Patterns frequently extend across wide surfaces, making alignment critical. Any distortion becomes immediately visible in finished installations. Fabric printing systems used for home applications must maintain registration over extended lengths. Heat fixation and ink bonding are also expected to support long-term exposure to light, cleaning, and environmental conditions.

Customization plays a growing role here as well. Interior designers increasingly request custom printed fabric tailored to specific spaces or themes. Custom textile printing allows patterns to be adjusted in scale or color without retooling entire production lines. The textile printer supports this flexibility by integrating digital design control with stable material handling.

Promotional and Industrial Fabrics

Promotional and industrial applications prioritize durability and versatility over aesthetic subtlety. Banners, flags, event backdrops, and branded textiles must withstand handling, transport, and environmental exposure. Fabric printing in this segment often involves synthetic materials engineered for strength and weather resistance.

In promotional contexts, output quality must remain consistent across large runs and varied formats. Prints are expected to fold, roll, and deploy repeatedly without visible damage. A textile printer operating in this space must manage ink adhesion and color stability across non-traditional fabrics.

Industrial fabric applications extend beyond branding. Printed textiles may serve functional roles in safety signage, filtration, or technical coverings. In these cases, printing supports identification or instruction rather than decoration. Custom printed fabric enables information to be embedded directly into materials, reducing reliance on secondary labeling or assembly steps.

Custom Fabric Production

Custom production represents the most direct expression of digital fabric printing capabilities. This category includes small-batch manufacturing, artist collaborations, and on-demand services where each order may differ. Custom textile printing shifts emphasis from efficiency at scale to precision and adaptability.

Here, the textile printer operates as a bridge between digital design and physical output. Designers can adjust patterns, colors, or dimensions without reconfiguring mechanical systems. Custom printed fabric supports niche markets, limited editions, and localized manufacturing models that would be impractical under traditional setups.

Material diversity is common in this space. Cotton, silk, polyester blends, and specialty textiles may all pass through the same workflow. The printing system must adapt to each without compromising quality. This flexibility reinforces the role of the textile printer as a production tool rather than a fixed-purpose device.

Across these application areas, the textile printer is defined by its ability to translate digital intent into durable physical output. Fabric printing succeeds when technology aligns with material behavior and production reality. Rather than enabling abstract creativity, textile printing systems support practical use cases shaped by wear, scale, and operational demands.

Materials and Ink Considerations in Textile Printing

Material choice sets the operating boundaries of textile printing systems. Fabric is not a passive surface, and its structure determines how ink behaves at every stage of production. A textile printer works within these material constraints, adjusting mechanical control, ink delivery, and fixation to match the physical reality of textiles rather than imposing uniform assumptions.

Fabric Structure and Print Behavior

Different fabrics respond to printing in fundamentally different ways. Fiber composition, weave density, and surface finish influence how ink spreads, penetrates, and stabilizes. Natural fibers tend to absorb liquid more readily, while synthetic materials often require heat-driven bonding processes to secure color.

These behaviors are not secondary considerations. They directly affect edge sharpness, color depth, and long-term durability. In fabric printing workflows, the substrate dictates process limits rather than accommodating them.

Key material-driven factors include:

- Fiber type influencing ink absorption and bonding

- Weave density affecting ink spread and pattern clarity

Textile printing systems that ignore these variables may produce visually acceptable output initially, but failures often appear after washing, stretching, or exposure to light. This is why fabric printing cannot rely on standardized presets alone.

Ink Chemistry and Fixation

Ink selection is inseparable from material choice. Textile inks are designed to interact with fibers, not simply coat a surface. Pigment inks rely on binders to anchor color, offering broad compatibility but requiring precise fixation. Reactive and acid inks chemically bond with specific fibers, producing strong penetration at the cost of material flexibility. Disperse inks, widely used in digital textile printing, depend on heat to transfer dye into synthetic fibers.

A textile printer integrates ink delivery with curing as part of a single system. Heat is not merely a drying step; it activates chemical or physical bonding that determines whether color remains stable through use. Misalignment between ink type and fixation conditions often results in fading, bleeding, or surface cracking.

Durability becomes the practical benchmark. Output is judged not at the moment of printing, but after repeated handling. Textile printing workflows prioritize longevity because failure carries downstream costs far beyond reprinting.

Durability and Environmental Impact

Environmental considerations increasingly influence textile production decisions. Traditional textile printing methods consumed significant water and chemical resources, particularly during setup and washing stages. Digital textile printing reduces some of this burden by applying ink only where required and minimizing preparatory waste.

Sustainability in fabric printing emerges from system efficiency rather than isolated features. Reduced water usage, controlled energy consumption during fixation, and extended product lifespan all contribute to lower environmental impact. A textile printer operating efficiently affects resource use across the entire production cycle, not just at output.

Textile Printers Within the Specialized Printers Landscape

Printing systems are shaped by the materials they are built to handle. Within the broader ecosystem of specialized printers, textile systems occupy a distinct position defined by fabric behavior rather than output size or resolution. A textile printer belongs to this category because it addresses variability as a baseline condition, not an exception.

Positioning Among Specialized Printing Systems

Specialized printers exist to solve material-specific problems. Each category reflects a tight relationship between media characteristics and system design. Textile systems align with this logic through their focus on flexible, absorbent substrates.

Their position can be understood relationally:

- Label printers manage adhesive-backed media where cutting precision and repeatability dominate

- Large format printers prioritize scale and alignment on dimensionally stable materials

- Banner printers and flex printers emphasize durability across synthetic surfaces exposed to weather

- Photo printers optimize surface accuracy and color precision on coated media

- Thermal printers and receipt printers focus on speed and transactional output rather than longevity

A fabric printer operates under different assumptions. Fabric stretches, absorbs, and shifts under tension. These behaviors require controlled feed systems, specialized inks, and integrated fixation. A printing on fabric machine must treat material movement and ink interaction as core design problems rather than secondary adjustments.

Although textile systems may share physical scale with large format equipment, their workflows diverge. Rigid media tolerates surface application; textiles demand penetration and stabilization. This difference explains why textile systems are rarely combined with other categories despite superficial similarities.

From an internal linking perspective, these relationships are conceptual rather than functional. Textile printers sit alongside other specialized systems because they share industrial logic, not because they overlap in use. A textile printer is evaluated on how effectively it integrates with upstream design processes and downstream finishing stages, rather than on standalone specifications.

Within the specialized printers landscape, textile systems represent a category shaped by material complexity. Their relevance comes from managing variability at scale, a challenge that general-purpose printing technologies are not built to accommodate.

Challenges and Future Directions in Textile Printing

Textile printing systems operate under constraints that extend beyond image quality. A textile printer must maintain mechanical stability, chemical consistency, and workflow continuity across materials that rarely behave the same way twice. These demands create technical and operational challenges that shape how production environments are designed and scaled.

Material variability remains a persistent issue. Fabric composition, weave structure, and surface finish influence ink absorption and fixation in ways that cannot be fully standardized. Even within a single production run, subtle differences in tension or moisture can affect output consistency. Textile printing systems compensate through tighter control mechanisms, but this increases system complexity and maintenance requirements.

Operational pressure also comes from production economics. Shorter runs and frequent design changes reduce setup efficiency while increasing demand for accuracy. Digital textile printing addresses some of this tension by removing physical setup stages, yet it introduces its own challenges. Managing color consistency across different fabrics, controlling ink consumption, and synchronizing fixation stages require precise calibration and monitoring.

Workflow integration represents another constraint. Textile printing rarely exists as a standalone step. It connects upstream with design and pre-treatment processes and downstream with finishing, cutting, or assembly. A textile printer that performs well in isolation may struggle when integrated into broader production lines. Reliability over extended operation becomes as important as peak output quality.

Future development trends respond directly to these pressures. Automation is increasingly focused on material handling and process control rather than speed alone. Sensors, inline monitoring, and adaptive software aim to reduce variability by responding to fabric behavior in real time. Digital textile printing workflows continue to evolve toward tighter integration, allowing design data, ink delivery, and fixation parameters to function as a unified system.

The direction forward emphasizes stability and adaptability rather than disruption. Textile printing advances incrementally, shaped by production realities rather than speculative innovation.

Conclusion

Textile printing occupies a distinct position within the broader printing ecosystem because it operates under material constraints that general-purpose systems are not designed to manage. A textile printer exists to translate digital designs into durable fabric output while accounting for movement, absorption, and long-term use.

Across technologies and applications, the defining role of textile printing systems lies in their ability to integrate mechanical control, ink chemistry, and fixation into a cohesive workflow. Whether serving apparel, interiors, or industrial applications, fabric printing depends on consistent interaction between material and process rather than isolated technical specifications.

Within the printing landscape, the textile printer aligns with other specialized systems that address specific material challenges. Its relevance is measured by reliability across varied substrates and production conditions, not by convenience or compact design. Fabric printing continues to evolve as production models change, but its foundational logic remains rooted in managing variability at scale.

FAQs About Textile Printers

What is a cloth printing machine called?

A cloth printing machine is commonly referred to as a textile printer. In industrial contexts, it may also be described as a textile printing system or fabric printing machine, depending on configuration.

What are the three styles of textile printing?

The three broad styles include screen printing, digital textile printing, and hybrid approaches that combine elements of both depending on production needs.

What type of printer prints on fabric?

A textile printer is specifically designed to print on fabric. These systems handle material movement, ink penetration, and fixation in ways standard printers cannot.

What’s the difference between a regular printer and a sublimation printer?

A regular printer applies ink onto the surface of paper, while a sublimation printer uses heat to transfer dye into synthetic fibers. Sublimation is commonly used in fabric printing workflows.

Can I print on fabric with a normal printer?

Normal printers are not built for fabric printing. While experimental attempts exist, reliable and durable results require a textile printer designed to manage fabric behavior and ink fixation.