The sls 3d printer is rarely part of how most people think about 3D printing. The technology is usually imagined at a much smaller scale: a desktop machine, plastic filament, and parts made for testing ideas rather than producing anything critical. That image has become so dominant that it quietly defines what 3D printing is assumed to be—accessible, experimental, and largely informal.

This narrow view leaves out an entire side of additive manufacturing technology that developed for very different reasons. Industrial 3D printing did not emerge to make fabrication easier for individuals. It emerged to address problems inside manufacturing environments, where strength, repeatability, and geometric complexity matter more than simplicity. The machines, materials, and workflows reflect that priority.

Within this industrial context, polymer 3D printing takes on a different meaning. It is no longer about visual prototypes or quick iterations alone, but about producing parts that can function under real mechanical demands. The sls 3d printer belongs to this world, even though it is often discussed as if it were just a more advanced version of familiar desktop systems.

That misunderstanding becomes clearer when looking at adoption rather than perception. Market analysis from Reports & Insights estimates the global sls 3d printer market at roughly USD 675.5 million in 2024, with projections reaching around USD 5.53 billion by 2032. Growth at this scale reflects industrial integration, not casual use. Companies invest in SLS because it solves production challenges that traditional methods struggle with.

Seeing industrial 3D printing clearly requires letting go of the consumer narrative. SLS was not designed as a stepping stone for hobbyists. It was designed as a manufacturing tool, shaped by constraints that rarely exist on a desktop.

What Is an SLS 3D Printer?

An sls 3d printer is best understood through how it behaves in practice, not through a short definition. Selective laser sintering is built around a powder bed, where material is distributed in thin layers and fused using controlled laser energy. Rather than extruding or curing material, the process relies on heat to bond powder particles into solid form.

In real-world use, this approach changes the entire logic of printing. The surrounding powder supports each part as it is formed, which removes the need for separate support structures. This allows complex shapes, internal channels, and tightly packed assemblies to be produced in a single build. Design constraints that feel unavoidable in other systems simply do not apply in the same way.

This is why this printer type is classified as a powder bed fusion technology. The powder bed acts as both raw material and structural support, while the laser sintering process defines where solid material forms. Within sls additive manufacturing, this combination enables consistent mechanical behavior across parts, even when geometries vary significantly.

An sls 3d printer is therefore less about speed or convenience and more about control. Temperature stability, laser precision, and powder management are essential to achieving reliable results. Parts are not rushed out of the machine; they cool gradually within the powder bed, preserving dimensional accuracy and material integrity.

Understanding SLS Printers means recognizing it as a manufacturing system rather than a simple device. It translates digital geometry into functional polymer parts through a tightly managed interaction between energy and material—one that reflects industrial priorities from start to finish.

The Origins of Selective Laser Sintering Technology

Selective Laser Sintering did not emerge from the same motivations that later shaped consumer 3D printing. Its origins sit firmly inside engineering research, where the focus was not accessibility or ease of use, but manufacturing constraints that traditional processes struggled to solve. In the broader additive manufacturing history, SLS belongs to a period when researchers were asking how digital design could translate directly into functional parts without molds, tooling, or long setup times.

Conventional industrial manufacturing processes rely on economies of scale. Injection molding, for example, works exceptionally well once tooling exists, but it becomes inefficient when designs change frequently or production volumes remain low. Engineers faced a recurring problem: how to produce strong, geometrically complex polymer components without committing to expensive tooling for every iteration. Subtractive methods introduced their own limitations, especially when internal geometries or undercuts were involved.

SLS was developed inside this context of constraint. Engineering research environments were already experimenting with lasers, thermal control, and material behavior at a granular level. The idea of using a laser to fuse powdered material selectively was a response to very specific industrial questions: how to control material bonding precisely, how to support complex shapes during fabrication, and how to maintain mechanical integrity without secondary fixtures.

Early positioning of SLS reflected these priorities. It was not presented as a replacement for mass production, but as a complementary process within manufacturing workflows. Engineers viewed it as a way to bridge design and production, allowing parts to move from digital models to physical components without the usual delays. From the beginning, SLS was aligned with industrial needs rather than consumer curiosity, which explains why its evolution followed a different path from desktop printing technologies.

How an SLS 3D Printer Works

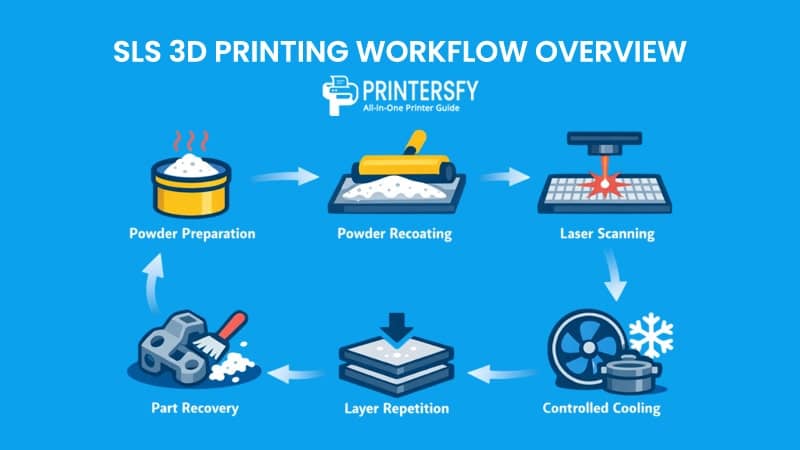

Before looking at individual components, it helps to step back and view the SLS workflow as a continuous manufacturing sequence rather than a collection of isolated steps. An sls 3d printer operates as a tightly coordinated system in which material preparation, thermal control, and laser interaction are all interdependent. Each phase sets the conditions for the next, and small variations can affect the final outcome.

To make that process easier to follow, the workflow below outlines how SLS 3D printing typically unfolds inside an industrial machine—from powder preparation to completed parts ready for post-processing.

SLS 3D Printing Workflow Overview

| Stage | Process Description | Purpose in Manufacturing |

|---|---|---|

| Powder preparation | Polymer powder is loaded and preheated close to sintering temperature | Ensures thermal stability and consistent fusion |

| Powder recoating | A thin layer of powder is spread evenly across the build platform | Creates a uniform surface for laser exposure |

| Laser scanning | Laser selectively sinters areas based on digital geometry | Forms solid cross-sections of the part |

| Layer repetition | Build platform lowers and new powder layers are applied | Enables layer by layer manufacturing |

| Controlled cooling | Completed build cools gradually inside the powder bed | Prevents warping and internal stress |

| Part recovery | Finished parts are removed and excess powder is reclaimed | Completes the cycle and supports material reuse |

With this sequence in mind, the individual elements of the system—powder bed, laser, and layer-by-layer construction—become easier to understand in context rather than in isolation.

The Powder Bed System Explained

An sls 3d printer operates around a powder bed system that defines both the material supply and the structural environment for each build. Instead of feeding material through a nozzle, the machine spreads a thin, even layer of polymer powder across a build platform. This powder bed system is carefully controlled for temperature and consistency, as both factors directly influence part quality.

Before printing begins, the powder is typically heated close to its sintering point. This preheating step reduces the amount of energy the laser must deliver later and helps maintain uniform thermal conditions. In an sls 3d printer, temperature stability is not a background detail; it is a core requirement that affects bonding strength and dimensional accuracy throughout the sls printing process.

Once the initial layer is prepared, the system is ready for selective fusion. At this stage, the powder bed is more than just material—it becomes an active component of the manufacturing environment, supporting parts as they form and preventing deformation during fabrication.

The Role of the Laser in the Sintering Process

The laser is the defining element of an sls 3d printer, but its role is often misunderstood. The laser does not fully melt the powder. Instead, it delivers controlled thermal energy that causes particles to fuse at their contact points. This distinction is central to the laser sintering process and influences how parts behave once completed.

As the laser scans across the powder bed, it follows the cross-sectional geometry of the part for that specific layer. Areas exposed to the laser solidify, while surrounding powder remains loose. Precision here is critical. Laser power, scan speed, and path strategy must work together to ensure consistent bonding without overheating the material.

This controlled interaction between energy and material is what separates SLS from other additive methods. In an sls 3d printer, the laser does not impose shape mechanically. It defines shape thermally, allowing complex geometries to emerge without physical constraints. This approach is particularly effective for polymer components that require balanced strength and flexibility.

Layer-by-Layer Manufacturing Without Support Structures

After a layer is scanned and fused, the build platform lowers slightly, and a fresh layer of powder is spread across the surface. This layer by layer manufacturing cycle repeats until the part is complete. Each new layer bonds to the one below it, creating a solid structure embedded within the powder bed.

One of the most significant outcomes of this approach is the absence of support structures. In an sls 3d printer, the surrounding powder naturally supports overhangs, internal channels, and complex features as they form. This eliminates the need for additional material that must later be removed, simplifying both design and post-processing.

The lack of supports changes how engineers think about geometry. Designs can prioritize function rather than printability, allowing features such as lattice structures or internal voids to exist without compromise. This is why SLS is often chosen for parts that must perform mechanically rather than simply demonstrate form.

Once printing is complete, the entire build cools gradually inside the machine. This cooling phase is essential. Rapid temperature changes could introduce warping or internal stress, so an sls 3d printer treats cooling as part of the process rather than an afterthought. When the build is finally removed, parts are excavated from the powder bed, and excess powder is recovered for reuse.

Viewed as a whole, the sls printing process is not a sequence of isolated steps but a tightly controlled system. Powder distribution, laser interaction, and thermal management work together to produce parts that reflect industrial expectations. This integrated approach explains why an sls 3d printer occupies a distinct position in additive manufacturing, shaped by the demands of production rather than convenience.

Materials Used in SLS 3D Printing

Material choice tends to stay in the background when SLS is discussed, even though it quietly shapes almost everything the process can deliver. The way a part behaves after printing—how strong it feels, how it flexes, how it holds its shape—has as much to do with the powder as it does with the machine. Over time, this is why a small group of polymers has become closely associated with SLS.

Why Nylon and Polyamide Dominate SLS

Most discussions of SLS materials quickly converge on one family: polyamides. In nylon powder 3D printing, these materials have proven to be consistently reliable across a wide range of applications. Their dominance is not accidental. Polyamide SLS materials combine thermal stability, mechanical strength, and predictable behavior during sintering, which makes them well suited to powder-based manufacturing.

Nylon powders flow evenly during recoating, absorb laser energy in a controlled way, and bond reliably from layer to layer. This balance is difficult to achieve with many other polymers. Materials that are too brittle tend to crack during cooling, while those that soften too easily can lose dimensional definition. Polyamide sits in a narrow window where fusion is reliable without sacrificing structural integrity.

Another reason polyamide SLS materials are favored lies in reuse. Unfused powder surrounding the part can often be reclaimed and mixed with fresh material. While reuse ratios vary depending on application and quality requirements, the ability to recycle powder supports more stable production workflows and reduces material waste—an important consideration in industrial environments.

Over time, this reliability has reinforced a feedback loop. As more manufacturers adopt nylon-based powders, machine parameters, post-processing methods, and design guidelines continue to mature around them. The result is a material ecosystem that feels stable and predictable, which is exactly what industrial additive manufacturing demands.

Material Properties and Mechanical Behavior

Once sintered, polyamide parts exhibit mechanical properties that align closely with functional requirements. The mechanical properties of SLS prints tend to be more uniform than those produced by many other additive processes, particularly along different axes. Because bonding occurs thermally rather than through deposited strands, parts do not inherit the same directional weaknesses often seen elsewhere.

Durability is one of the most cited benefits. SLS nylon parts can withstand repeated mechanical stress, making them suitable for enclosures, brackets, housings, and other components that experience real-world loads. Flexibility is also present to a controlled degree. Rather than snapping under stress, many polyamide parts deform slightly before failure, which is desirable in functional designs.

Thermal behavior matters as well. SLS materials are chosen not only for how they print, but for how they behave after printing. Polyamides maintain dimensional stability across moderate temperature ranges and resist creep better than many alternatives. This combination of strength, resilience, and thermal performance explains why SLS has become closely associated with functional polymer parts rather than purely visual models.

Characteristics of SLS Printed Parts

Material choices only matter insofar as they shape the final result. What ultimately defines SLS in practice is how the printed part behaves once it leaves the machine. Strength, surface texture, and dimensional stability do not exist in isolation; they interact, and trade-offs are unavoidable. This balance is where expectations around SLS parts are formed.

Strength, Durability, and Isotropic Properties

One of the defining traits of SLS print quality is its relative isotropy. Because powder particles fuse uniformly throughout the part, strength is more evenly distributed in all directions. This isotropic strength reduces the risk of failure along layer boundaries, a concern common in other additive processes.

In practical terms, this means SLS parts can be trusted in load-bearing roles where orientation should not dictate performance. Durability follows naturally from this consistency. Parts resist cracking, splitting, and delamination, even under repeated stress. For many industrial users, this reliability matters more than achieving the highest possible tensile strength on paper.

That said, SLS parts are not indestructible. Their strength must still be evaluated within the context of material choice, wall thickness, and design geometry. The advantage lies in predictability: engineers can design with confidence that performance will remain consistent across builds.

Surface Finish and Dimensional Accuracy

Surface finish is where expectations often need adjustment. SLS parts typically emerge with a slightly grainy texture, a direct result of the powder-based process. This surface finish is not a defect; it is a characteristic. For many functional applications, the texture is acceptable or even beneficial, improving grip or bonding with coatings.

When smoother finishes are required, post-processing techniques such as bead blasting, tumbling, or coating are commonly applied. These steps refine appearance without altering the underlying structure of the part. Importantly, surface refinement is optional, not mandatory, depending on the application.

Dimensional accuracy in SLS is generally consistent across batches when parameters are well controlled. Parts maintain their shape during cooling thanks to the surrounding powder bed, which minimizes warping. While extremely tight tolerances may still require secondary machining, SLS offers a level of dimensional stability that supports repeatable production.

Key Characteristics of SLS Printed Parts

| Property | Typical Behavior |

|---|---|

| Strength | High, near-isotropic |

| Surface texture | Slightly grainy |

| Dimensional stability | Consistent |

Advantages of Using an SLS 3D Printer

The advantages of SLS tend to reveal themselves through use rather than specification sheets. Many of its benefits are not standalone features, but direct consequences of how the process works and what it prioritizes. When viewed through that lens, an sls 3d printer offers strengths that make sense in industrial contexts, even if they are less obvious to casual observers.

Design Freedom and Complex Geometry

Design freedom is often mentioned when discussing additive manufacturing, but SLS approaches it in a particularly practical way. Because parts are formed inside a powder bed, complex geometries without supports are not an exception; they are a natural outcome of the process. Overhangs, internal channels, lattice structures, and nested components can be produced without adding material solely for temporary support.

This freedom changes how engineers approach design problems. Instead of simplifying geometry to accommodate the manufacturing process, they can focus on function first. Weight reduction through internal structures, airflow optimization inside enclosed parts, or the consolidation of multiple components into a single assembly all become realistic options. In these cases, the advantages of SLS 3D printing are less about novelty and more about removing long-standing constraints.

An sls 3d printer also allows multiple parts to be arranged throughout the build volume without concern for orientation-related failures. Since strength is not heavily dependent on print direction, designers gain flexibility in how builds are packed and optimized. This efficiency matters in industrial settings where build volume translates directly into cost and throughput.

Functional End-Use Parts

Another advantage lies in what happens after printing. Parts produced on an sls 3d printer are often ready to be used as functional components rather than visual stand-ins. The combination of material properties and isotropic strength supports real mechanical loads, making SLS suitable for enclosures, clips, brackets, housings, and other parts that must perform reliably.

This capability shortens the path from design to deployment. Instead of treating additive manufacturing as a prototyping-only step, companies can move directly into low- to medium-volume production. For certain applications, the distinction between prototype and final part becomes less meaningful, especially when designs are expected to evolve over time.

It is worth noting that these advantages are contextual. SLS excels when complexity and functionality justify the process. The technology does not try to compete with mass production methods on unit cost at scale. Its value lies in producing parts that would otherwise be difficult, slow, or expensive to manufacture through traditional means.

Limitations and Challenges of SLS Technology

The strengths of SLS are balanced by real limitations. Ignoring them leads to unrealistic expectations and poor technology choices. Understanding the disadvantages of SLS 3D printing is essential for evaluating when it makes sense—and when it does not.

Cost and Operational Complexity

Cost is often the first barrier. An sls 3d printer represents a significant investment, not only in the machine itself but in supporting infrastructure. Controlled environments, material handling systems, and trained operators all contribute to sls production costs. Unlike desktop systems, SLS is not designed for casual setup or ad-hoc use.

Operational complexity extends beyond hardware. Parameter tuning, temperature management, and build preparation require experience. Mistakes are not always immediately visible, and material waste can accumulate quickly if workflows are not well controlled. For organizations without consistent demand or technical expertise, these factors can outweigh the benefits.

This complexity also affects scalability. While SLS is well suited to certain production volumes, it does not scale infinitely in a linear way. At higher volumes, traditional manufacturing methods often regain their cost advantage, especially when designs stabilize.

Post-Processing and Powder Handling

Printing is only part of the workflow. Post-processing SLS parts introduces its own challenges. Once a build is complete, parts must be removed from the powder bed, cleaned, and sometimes finished. Post-processing SLS parts typically involves depowdering, surface treatment, and, in some cases, secondary machining.

Powder handling deserves particular attention. Fine polymer powders require careful storage and controlled reuse to maintain quality. Contamination, moisture absorption, and inconsistent mixing ratios can all affect results. These factors add operational overhead that is easy to underestimate when focusing solely on print capabilities.

Taken together, these limitations explain why SLS is not universally practical. It excels in specific scenarios but demands discipline and infrastructure to deliver consistent value.

Industrial Applications of SLS 3D Printing

The adoption of SLS across industries is driven less by hype than by fit. Organizations turn to industrial SLS printing when its characteristics align with their production needs, especially where flexibility and performance outweigh simplicity.

Prototyping vs End-Use Production

SLS has long been used for prototyping, but its role has expanded. In sls prototyping, the ability to produce durable parts quickly allows teams to test designs under realistic conditions. Fit, function, and mechanical behavior can all be evaluated without waiting for tooling.

Where SLS becomes particularly interesting is at the boundary between prototyping and production. End-use parts SLS workflows make sense when volumes are moderate and designs continue to evolve. Instead of freezing a design to justify tooling costs, companies can iterate while still delivering functional components.

This flexibility supports agile manufacturing strategies. Design changes do not require starting over; they can be incorporated into the next build with minimal disruption.

Why Certain Industries Prefer SLS

Industries that adopt SLS tend to share similar priorities. They value performance, customization, and speed over sheer volume. In sectors such as industrial equipment, healthcare devices, and specialized consumer products, SLS enables tailored solutions without prohibitive setup costs.

Market adoption reflects this pattern. According to an industry report from VoxelMatters, over 55% of SLS systems sold globally come from a single dominant platform category. This concentration suggests that users are standardizing around proven industrial ecosystems rather than experimenting broadly. The focus is on reliability and integration, not novelty.

An sls 3d printer fits best where manufacturing demands are complex but controlled. It supports production strategies that prioritize adaptability and functional performance, offering a clear role within modern industrial workflows without trying to replace every other manufacturing method.

Cost Reality of Owning and Operating an SLS 3D Printer

Discussions about cost often stop at the machine itself, but that view rarely matches reality. The sls 3d printer sits inside a broader system of equipment, materials, and processes that determine whether it makes economic sense over time. Understanding those factors is essential before treating SLS as a production option.

Beyond Machine Price

The upfront price of an sls 3d printer is only the most visible part of the investment. Industrial systems require controlled environments, stable power, ventilation, and space designed for safe powder handling. These requirements add to the initial setup long before the first part is printed. For many organizations, the supporting infrastructure rivals the machine cost itself.

Material expenses also behave differently from filament or resin-based systems. Polymer powders must meet strict specifications to maintain consistency, and while unused powder can often be recycled, it cannot be reused indefinitely without careful blending and quality control. This makes sls 3d printer cost less predictable if workflows are not well managed.

Maintenance and expertise are another layer. Industrial SLS systems depend on calibration, thermal stability, and optical precision. Skilled operators are not optional; they are part of the cost structure. In practice, the machine is only as reliable as the process around it, and that process requires ongoing investment.

Workflow and Production Economics

Where SLS begins to justify its cost is in how it supports certain production strategies. Industrial 3D printing cost factors shift when tooling is removed from the equation. For low- to medium-volume production, the ability to move directly from digital design to finished parts can offset higher per-part costs.

Batch efficiency also matters. Multiple components can be nested throughout the build volume, allowing a single run to produce a wide variety of parts. When demand is diverse and change is frequent, this flexibility becomes economically meaningful. In these scenarios, SLS is less about minimizing unit cost and more about reducing delays, inventory, and retooling.

That said, SLS is not universally economical. When volumes increase and designs stabilize, traditional manufacturing often becomes more cost-effective. SLS works best when production economics are shaped by variability rather than scale.

Position of SLS Among 3D Printing Technologies

Choosing a 3D printing method is rarely about which technology is “better.” It is about context. The sls 3d printer occupies a specific position within the additive manufacturing landscape, defined by what it does well and where its trade-offs lie.

When SLS Makes Sense

SLS makes sense when functional performance and geometric freedom are central requirements. Parts that must withstand mechanical stress, incorporate internal features, or exist in multiple variants benefit from the powder-based process. In these cases, the sls 3d printer supports production goals that would be difficult to achieve with other methods.

SLS is also well suited to workflows where designs evolve. Because there is no tooling to amortize, changes can be introduced without restarting the production process. This flexibility is valuable in industrial environments where iteration is ongoing rather than occasional.

When FDM or SLA Is the Better Choice

There are many situations where SLS is unnecessary. For early-stage prototyping, concept validation, or visual models, FDM or SLA often provide faster and more economical results. These technologies are easier to operate, require less infrastructure, and support rapid experimentation.

In the context of sls vs fdm 3d printing, FDM excels when simplicity and low cost matter more than mechanical consistency. Similarly, sls vs sla 3d printing comparisons often favor SLA when surface detail and fine features are the priority. Choosing the right 3D printers technology means matching requirements to capabilities, not defaulting to the most industrial option available.

Common Mistakes in Choosing SLS

One common mistake is treating SLS as a universal upgrade. The sls 3d printer is sometimes selected because it appears more advanced, even when its strengths are unnecessary. This leads to underutilized equipment and inflated costs.

Another mistake lies in underestimating operational demands. Without disciplined workflows, powder management, and skilled operators, SLS systems struggle to deliver consistent results. In those cases, the technology’s advantages remain theoretical rather than practical.

Contextual Comparison of SLS, FDM, and SLA

| Aspect | SLS 3D Printer | FDM 3D Printer | SLA 3D Printer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Material form | Powder | Filament | Liquid resin |

| Support structures | Not required | Required | Required |

| Typical use | Functional parts | Prototyping | High-detail parts |

The Role of SLS in Modern Manufacturing

In practice, SLS is rarely used in isolation. It operates within a broader manufacturing environment, shaped by how products are designed, produced, and adapted over time. From that perspective, its role becomes easier to place.

Digital Manufacturing and Low-Volume Production

SLS has settled into modern manufacturing not as a replacement for established methods, but as a connective layer between design and production. Within digital manufacturing, it supports workflows where data moves faster than tooling and where variation is expected rather than avoided. That role becomes clearer in environments shaped by frequent design changes, short product cycles, and mixed demand.

Industrial additive manufacturing systems like SLS fit naturally into low-volume production because they remove the traditional penalty for complexity. Parts do not need to be simplified to justify molds, nor do small batches carry the same overhead they would in conventional processes. This allows manufacturers to treat production as an extension of design—iterative, responsive, and closely tied to real use conditions.

What distinguishes SLS in this ecosystem is reliability. It provides a stable way to produce functional polymer parts with consistent behavior, even as geometries change. That consistency enables planning. Teams can qualify parts, document processes, and integrate SLS into broader manufacturing strategies without treating each build as an experiment.

SLS also complements, rather than competes with, other methods. In many workflows, it sits alongside machining, molding, or assembly operations, filling gaps where flexibility matters more than scale. The result is a more modular approach to manufacturing, where different technologies are applied according to need rather than hierarchy.

Seen this way, SLS contributes to a manufacturing mindset that values adaptability. It supports production that is smaller, smarter, and closer to the point of design—without requiring the abandonment of established industrial practices.

Conclusion

The sls 3d printer makes sense only when viewed in context. It is not a shortcut to cheaper production, nor a universal upgrade to other 3D printing methods. Its value lies in how precisely it addresses a specific set of manufacturing challenges: complexity without tooling, functional performance in polymer parts, and production workflows that can change without friction.

Understanding SLS requires moving beyond feature lists and comparisons. The technology reflects priorities that come from industrial use—repeatability, material behavior, and process control. Those priorities explain both its strengths and its limitations. Where flexibility and function matter more than scale, the sls 3d printer earns its place. Where simplicity or volume dominate, other methods remain more practical.

What SLS ultimately represents is a different way of thinking about production. It treats manufacturing as something that can remain closely linked to design, even as parts move into real use. In that sense, the sls 3d printer is less about disruption and more about alignment—aligning digital intent with physical output, without forcing either to compromise.

Seen clearly, SLS is not a promise of what manufacturing might become. It is a reflection of how certain parts are already being made today, quietly and deliberately, within a broader industrial ecosystem.

FAQs About SLS 3D Printer

What is SLS in 3D printing?

SLS stands for Selective Laser Sintering. It is a 3D printing process that uses a laser to fuse powdered polymer material into solid parts, layer by layer, inside a controlled powder bed.

What material is used in SLS 3D printing?

SLS commonly uses polymer powders, especially nylon and other polyamide-based materials. These powders are chosen for their stable thermal behavior and balanced mechanical properties.

Is SLS considered 3D printing?

Yes. SLS is a form of additive manufacturing and is firmly part of the broader 3D printing family, although it is designed primarily for industrial rather than consumer use.

Why is SLS printing so expensive?

SLS involves high equipment costs, controlled environments, skilled operation, and material handling. The expense reflects process complexity, not just the machine itself.

What is the cost of SLS 3D printing?

Costs vary widely depending on machine class, materials, and production volume, but SLS is generally positioned as a professional and industrial manufacturing solution.