SLA 3D printing exists because not every printed object is evaluated by strength, speed, or production volume. In many professional workflows, visual accuracy and surface clarity carry their own weight. Models are judged by how closely they reflect a digital design, how cleanly edges resolve, and how confidently small details appear without correction. An SLA 3D printer was developed for this kind of expectation, where precision is treated as a starting point rather than a bonus.

Resin 3D printing approaches fabrication from a different direction than most additive methods. Instead of moving softened material into place, the process relies on light to define solid form inside a liquid medium. That choice affects how parts behave once they leave the machine. Surfaces feel continuous rather than stacked, curves appear intentional rather than approximated, and fine features remain legible without aggressive post-processing. High-detail 3D printing is not an accidental outcome here; it is embedded in the logic of the process itself.

Photopolymer technology has grown alongside industries that depend on early-stage accuracy. In dental modeling, product design, and form-driven prototyping, a part often needs to communicate shape and proportion long before it needs to perform mechanically. In these contexts, a clean surface and faithful geometry are functional requirements. An SLA 3D printer fits naturally into this space because it narrows the gap between what exists on a screen and what can be held in the hand.

This article is written for readers who already see 3D printing as a working tool rather than a novelty. It assumes familiarity with additive manufacturing in general and focuses instead on why resin-based systems remain relevant as other technologies mature. For designers, engineers, and specialists deciding where precision belongs in their workflow, understanding the role of an SLA 3D printer begins with understanding what it is designed to prioritize and where its strengths become visible.

What Is an SLA 3D Printer?

An SLA 3D printer is based on stereolithography, one of the earliest additive manufacturing methods to reach practical use. Rather than depositing material line by line, the system forms objects by selectively solidifying liquid resin using controlled light exposure. This approach defines stereolithography 3D printing at its core and explains why its results differ so clearly from other printing methods.

The Core Idea Behind Stereolithography

The foundation of this type of printer lies in liquid resin curing. A photosensitive resin remains fluid until it is exposed to a specific wavelength of light, at which point it hardens with a clearly defined boundary. Through UV light curing, each layer is formed as a complete surface rather than a series of overlapping paths. After one layer solidifies, the build platform shifts and fresh resin flows into place, ready for the next exposure.

What distinguishes an SLA 3D printer at this stage is optical control. Accuracy depends on how precisely light can be delivered and stopped, not on nozzle diameter or material flow. This allows subtle curves, thin walls, and fine surface features to survive the printing process with minimal loss. Instead of compensating for the behavior of molten plastic, designers can focus on geometry and proportion, trusting that the process will preserve intent.

Because the curing happens across an entire layer at once, surfaces emerge with fewer visible transitions. The result is a printed object that feels resolved rather than assembled, particularly when viewed at close range. This characteristic explains why stereolithography continues to be associated with visual fidelity and dimensional clarity.

How SLA Differs From Filament and Powder-Based Printing

The role of an SLA 3D printer becomes clearer when it is placed alongside other common technologies. Filament-based systems rely on extrusion, heating thermoplastic material and laying it down in visible paths. In an extrusion vs resin comparison, the trade-off is straightforward. Filament printing favors versatility, material durability, and ease of use, but surface texture and layer lines are unavoidable byproducts of the process.

Powder-based systems follow a different logic altogether. In a typical powder bed fusion overview, fine material is spread into thin layers and selectively fused using heat or lasers. These technologies excel at producing strong, complex parts, especially in industrial environments. However, surface texture, grain, and post-processing demands differ significantly from what resin-based printing delivers.

Within this ecosystem, an SLA 3D printer does not attempt to replace filament or powder-based machines. Its role is narrower and more deliberate. It exists to translate digital models into physical objects with minimal visual distortion, particularly during early design and validation stages. For applications where surface quality, proportion, and fine detail matter more than raw durability, this explains why the SLA 3D printer continues to hold a defined and practical place.

How Does SLA 3D Printing Work?

SLA 3D printing works by controlling a single decision repeatedly: where liquid resin should become solid, and where it should remain untouched. Unlike extrusion-based systems that move material into position, an SLA 3D printer defines shape by limiting exposure. Light is not used to add material, but to draw boundaries inside a resin bath. That distinction shapes the entire workflow.

This approach gives SLA a different character from most additive manufacturing processes. Parts are not built through stacked lines or fused particles. They emerge from a sequence of controlled transformations, each one governed by optical precision. The result is a workflow that favors surface continuity and geometric clarity, even before post-processing begins.

An SLA 3D printer operates through three tightly connected stages. First, resin is managed inside a controlled vat environment. Second, geometry is formed through repeated curing cycles. Finally, the printed object is stabilized through post-processing. None of these stages functions independently. Together, they explain why SLA behaves the way it does.

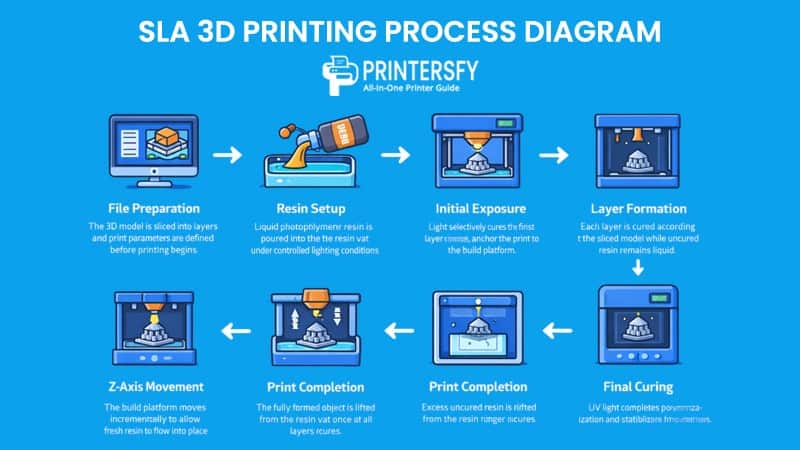

SLA 3D Printing Process Steps by Steps

| Stage | Description | Key Elements Involved |

|---|---|---|

| File Preparation | The 3D model is sliced into layers and print parameters are defined before printing begins. | Slicer software, layer settings, exposure values |

| Resin Setup | Liquid photopolymer resin is poured into the resin vat under controlled lighting conditions. | Resin vat, photopolymer resin |

| Initial Exposure | Light selectively cures the first layer, anchoring the print to the build platform. | Build platform, light source |

| Layer Formation | Each layer is cured according to the sliced model while uncured resin remains liquid. | Vat photopolymerization, laser or projected light |

| Z-Axis Movement | The build platform moves incrementally to allow fresh resin to flow into place. | Z-axis mechanism, build platform |

| Print Completion | The fully formed object is lifted from the resin vat once all layers are cured. | Build platform, completed part |

| Resin Washing | Excess uncured resin is removed from the surface of the printed object. | Cleaning solvent, wash station |

| Final Curing | UV light completes polymerization and stabilizes material properties. | UV curing chamber |

Vat Photopolymerization Explained

At the center of SLA printing is vat photopolymerization. A resin vat holds liquid photopolymer resin in a light-controlled environment, preventing accidental curing. Suspended above or within this vat is the build platform, which acts as the anchor point for the part as it forms.

During printing, the SLA 3D printer exposes specific regions of resin at the interface between the vat and the build platform. When exposed, the resin undergoes a chemical reaction and solidifies. Everywhere else, the resin remains liquid. This selective behavior allows the printer to create complex shapes without filling the entire volume with solid material.

The interaction between the resin vat and the build platform must remain consistent throughout the print. The distance between them determines layer thickness and directly affects surface quality. Because resin flows freely, the system depends on mechanical stability rather than pressure. Any variation in movement or alignment can translate into visible defects.

Vat photopolymerization also reduces the need for traditional support strategies. Liquid resin naturally supports overhangs during printing, allowing geometry to form gradually. This characteristic contributes to the smooth surfaces commonly associated with SLA output.

Layer-by-Layer Curing Process

Once the printing cycle begins, the SLA 3D printer builds geometry through a repeated curing sequence. Each layer corresponds to a digital slice of the original model. That slice defines where light should be applied and where resin should remain liquid.

In laser-based systems, laser curing traces the shape of each layer across the resin surface. The laser moves with controlled speed and intensity, solidifying resin only where geometry exists. Other systems expose entire layers at once, but the underlying principle remains unchanged. Light defines form.

Layer resolution determines how much detail survives the process. Thinner layers reduce visible stepping and preserve subtle transitions between surfaces. Thicker layers shorten print time but introduce more pronounced transitions. An SLA 3D printer allows users to choose this balance based on the needs of the part.

After a layer is cured, the build platform shifts along the Z-axis. This Z-axis movement creates space for fresh resin to flow into position before the next exposure cycle begins. Precision at this stage is critical. Small inconsistencies can accumulate over hundreds or thousands of layers, affecting dimensional accuracy.

Because material is cured rather than deposited, boundaries between layers tend to blend more naturally. This is why SLA printer parts often appear smoother than those produced by extrusion-based methods, even before finishing.

Post-Processing and Final Curing

When printing ends, the object that emerges from the SLA 3D printer is complete in shape but not in material state. The resin has been partially cured, but it has not yet reached its final properties. Post-processing completes the transformation.

The first step is resin washing. Excess liquid resin clings to the surface and must be removed to prevent residue or surface defects. Washing dissolves uncured resin while preserving fine detail, preparing the part for final stabilization.

After washing, the part undergoes post-curing. Exposure to controlled ultraviolet light completes the polymerization process. This step improves surface hardness, dimensional stability, and material consistency. It also ensures that the part behaves as intended once removed from the workflow.

According to official specifications published for the Formlabs Form 3, SLA printers support layer heights as fine as 25 microns, allowing for exceptionally smooth surface finishes and fine details. This information, documented by the University of Michigan Digital Fabrication Studio, highlights how precise layer control directly influences final output quality.

Core SLA Technologies (Vat Photopolymerization Family)

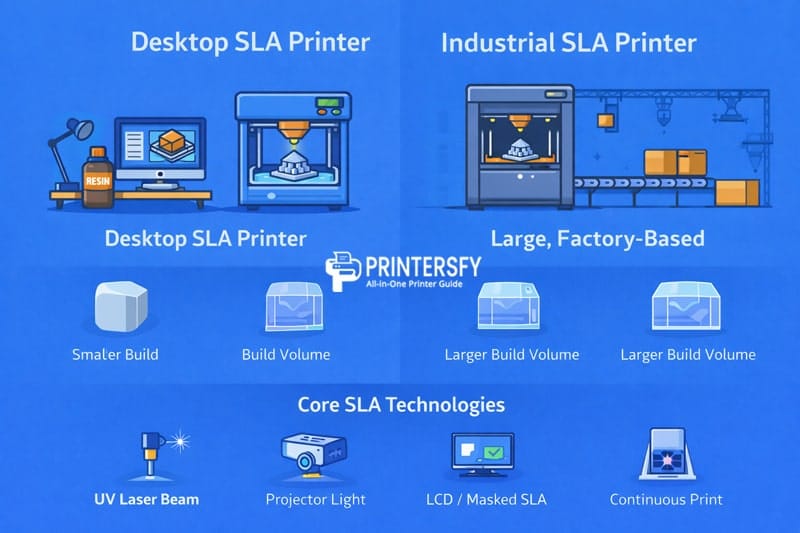

Vat photopolymerization is not a single implementation but a family of related approaches that all rely on the same fundamental idea: liquid resin becomes solid when exposed to controlled light. Within this family, different systems vary in how light is delivered, how layers are formed, and how quickly the process can move from one exposure to the next. These variations explain why two machines can both be described as an SLA 3D printer while behaving very differently in practice.

At a conceptual level, every SLA-based system shares three constants. A photosensitive resin sits in a controlled environment, light exposure defines geometry, and uncured material remains liquid until it is needed or removed. Where these systems diverge is in the mechanics of exposure and motion. Those differences affect speed, consistency, cost, and the kinds of workflows each technology supports.

Laser-Based SLA (Classic Stereolithography)

Laser-based SLA is the most direct expression of stereolithography. In this approach, a focused UV laser traces each layer’s geometry across the resin surface. The laser moves point by point, curing only where it passes. This point-by-point curing method places a strong emphasis on precision, as the laser can be controlled with extreme accuracy.

Because the laser follows the exact contours of each layer, classic stereolithography has long been associated with high surface fidelity and predictable dimensional results. An SLA 3D printer built around a UV laser excels when geometry includes fine edges, thin walls, or subtle transitions. The trade-off is time. Tracing complex layers point by point can slow down production, especially for larger parts or dense models.

Despite this limitation, laser-based systems remain relevant in environments where consistency matters more than throughput. Industrial labs and engineering workflows often favor this approach because it produces repeatable results across different builds. The precision of the laser also makes it easier to fine-tune exposure parameters for specific resins, which can improve surface finish and reduce post-processing effort.

DLP (Digital Light Processing)

DLP systems approach the same resin-curing problem from a different angle. Instead of tracing geometry with a laser, they use projector-based curing. A digital projector flashes an entire layer image onto the resin surface at once, curing all exposed areas simultaneously. This layer projection method dramatically changes how time scales with part complexity.

With DLP, the exposure time for a layer remains the same regardless of how much geometry is present. Whether the layer contains a single feature or dozens, the projector cures everything in one step. This makes DLP attractive for applications where speed and batch production matter. Multiple parts can often be printed together without significantly increasing build time.

The behavior of an SLA 3D printer using DLP is shaped by the projector’s resolution. Pixel size determines the smallest detail that can be reproduced, which introduces a different kind of constraint compared to laser spot size. While surface quality remains high, very fine features may show subtle pixelation under close inspection. In many practical workflows, this trade-off is acceptable, especially when balanced against faster print cycles.

DLP systems are commonly found in professional environments where predictable layer times and efficient throughput are priorities. They occupy a middle ground between classic SLA precision and newer, cost-focused implementations.

LCD / Masked SLA

LCD-based systems, often referred to as masked SLA, build on the same principle as DLP but replace the projector with an LCD screen. The screen acts as a mask, selectively blocking or allowing light to pass through to the resin below. This LCD masking approach has made resin printing more accessible by reducing hardware complexity and cost.

In these systems, a uniform light source shines through the LCD panel, which displays the layer image. The exposed regions cure while masked areas remain liquid. Because the screen controls exposure, layer projection happens in a single step, similar to DLP. This makes LCD systems efficient and well suited for desktop resin printers.

An SLA 3D printer based on LCD technology often prioritizes affordability and compact design. These machines have played a major role in expanding resin printing beyond industrial settings. However, the lifespan and resolution of the LCD panel become important considerations. Over time, screens can degrade, and pixel size still defines the lower limit of detail reproduction.

Even with these constraints, LCD systems deliver impressive results for their size and cost. They are widely used in design studios, dental labs, and small workshops where high-detail output is needed without industrial-scale investment.

CLIP (Continuous Liquid Interface Production)

CLIP represents a more radical departure from traditional layer-based motion. Instead of curing one layer, stopping, and moving the build platform, CLIP enables continuous printing. This is achieved through an oxygen-permeable window that creates a thin “dead zone” where resin does not cure, even when exposed to light.

By maintaining this uncured interface, the system allows the part to rise continuously from the resin vat while light exposure happens without interruption. The result is a smooth, uninterrupted build process that significantly increases speed. In industrial resin printing, this approach reduces mechanical stress and shortens production cycles.

An SLA 3D printer using CLIP behaves differently from conventional systems. Layer lines become less pronounced, and surfaces can appear more uniform straight off the machine. The technology is typically reserved for controlled environments due to its complexity and reliance on specialized materials.

CLIP is less about accessibility and more about redefining production-scale resin printing. Its strengths become clear in manufacturing contexts where speed, consistency, and surface quality must coexist.

Output Characteristics and Print Quality

The defining appeal of SLA printing lies in how parts look and feel once they are complete. Across different implementations, an SLA 3D printer consistently produces output that emphasizes clarity, smoothness, and geometric fidelity. These characteristics are not incidental; they are direct consequences of how light-based curing interacts with liquid resin.

Print quality in SLA is shaped by exposure control, layer thickness, and material behavior. While each technology within the vat photopolymerization family has its own nuances, they all share a common advantage in surface presentation.

Surface Finish and Resolution

Surface finish is often the first attribute noticed when evaluating SLA output. Because resin is cured in place rather than deposited, surfaces tend to appear continuous. Micron resolution settings allow layers to blend together visually, reducing the stepped appearance common in extrusion-based printing.

An SLA 3D printer operating at fine layer heights can produce smooth surfaces that require minimal finishing for visual applications. This makes SLA particularly suitable for display models, molds, and parts where appearance communicates function or intent. Even before sanding or polishing, the surface often reflects the original digital model with high fidelity.

Resolution also influences how light interacts with the final object. Sharp edges remain defined, and curved surfaces maintain their intended profile. These qualities are especially important in small-scale components, where imperfections are more noticeable.

Dimensional Accuracy and Detail Reproduction

Dimensional accuracy is another area where SLA excels. Because geometry is defined optically, fine features can be reproduced with a high degree of consistency. An SLA 3D printer is well suited for parts that include small text, intricate patterns, or tight tolerances.

Detail reproduction depends on stable exposure and precise motion. When these conditions are met, features that might be lost or softened in other processes remain intact. This reliability makes SLA a preferred choice for prototyping methods that require confidence in fit and proportion.

While resin parts may not always match the mechanical strength of powder-based alternatives, their visual and dimensional precision often outweighs that limitation during early design stages. In workflows where appearance and accuracy guide decisions, SLA output provides a clear reference point.

Practical Limitations and Trade-Offs of SLA Printing

SLA printing is often associated with precision and surface quality, but those strengths come with constraints that shape how the technology is used in practice. An SLA 3D printer is not designed to be universally efficient or convenient. Its value depends on whether its trade-offs align with the goals of a given workflow.

One of the most noticeable limitations appears after the print finishes. The post-processing workflow is not optional and cannot be rushed. Parts must be removed carefully, cleaned to eliminate uncured resin, and exposed to additional light to stabilize the material. Each step introduces time, handling, and the possibility of error. Compared to extrusion-based printing, where parts can often be used immediately, SLA demands more attention before a result is ready.

Resin handling is another practical consideration. Liquid photopolymer resin behaves differently from solid filament or powder. It requires controlled storage, careful pouring, and protection from unintended light exposure. Spills and contamination can affect print quality or damage equipment. These factors do not make SLA impractical, but they do require a more deliberate approach to setup and cleanup. For some users, this added complexity is a fair exchange for higher visual fidelity. For others, it becomes a barrier.

Printing speed limitations also play a role. While certain implementations can move quickly, an SLA 3D printer is generally slower when producing large or solid parts. Fine layer heights improve surface quality but extend build times. Increasing speed often means sacrificing resolution, which undercuts one of the main reasons SLA is chosen in the first place. As a result, SLA workflows tend to favor fewer, more intentional prints rather than high-volume output.

These trade-offs explain why SLA is rarely positioned as a general-purpose solution. It performs best when accuracy and appearance justify the additional effort. When evaluated in that context, the limitations are not flaws, but boundaries that define where the technology makes sense.

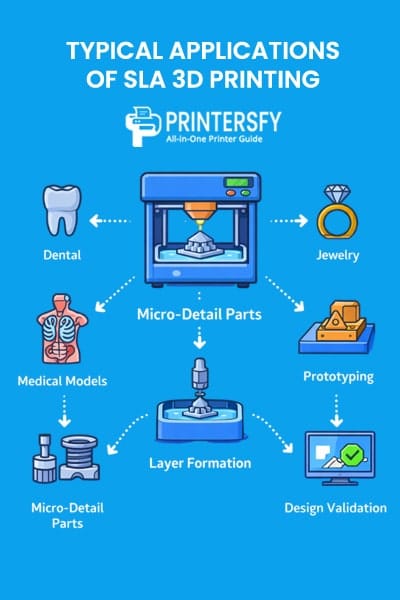

Typical Applications of SLA 3D Printing

SLA printing is used most effectively when its strengths match the demands of the application. Across industries, the technology appears most often in roles where visual clarity, fine detail, and predictable geometry matter more than raw mechanical performance. An SLA 3D printer becomes valuable when it helps decision-making earlier in a process, before durability becomes the primary concern.

Dental and Medical Models

Dental and medical fields were among the earliest adopters of SLA, and they remain closely associated with the technology. Dental models require clean surfaces, accurate margins, and consistent scaling. Small deviations can affect fit, alignment, or interpretation. Resin-based printing supports these needs by producing dental models that closely reflect digital scans and design files.

In medical contexts, SLA is often used for anatomical references, guides, and visualization tools. These models are not typically load-bearing, but they must be dimensionally reliable. The ability of an SLA 3D printer to reproduce fine anatomical features makes it well suited for this role. The emphasis is not on strength, but on clarity and accuracy.

Jewelry and Micro-Detail Parts

Jewelry design highlights another area where SLA excels. Rings, pendants, and ornamental components often include fine textures and intricate forms that are difficult to reproduce through other printing methods. Resin printing allows designers to create casting patterns with clean edges and smooth transitions, reducing the need for manual correction.

Micro-detail parts benefit from the same characteristics. Small-scale components, decorative elements, and detailed figurines rely on visual precision. In these cases, surface quality directly affects perceived value. An SLA 3D printer supports this by maintaining detail that might be lost through extrusion or powder-based processes.

Prototyping and Design Validation

Prototyping is one of the most common uses of SLA printing. Design prototypes are often evaluated visually before they are tested mechanically. Proportions, surface flow, and ergonomic details all influence early decisions. SLA allows these aspects to be assessed with minimal distraction from layer artifacts or surface roughness.

In design validation workflows, the goal is not to test strength, but to confirm intent. An SLA 3D printer produces parts that closely resemble the final product in form, even if the material properties differ. This makes it easier for designers, engineers, and stakeholders to align on changes before moving to more expensive manufacturing methods.

Desktop SLA vs Industrial SLA Printers

SLA technology spans a wide range of machine scales, from compact systems designed for individual workspaces to large installations built for production environments. While both fall under the same technical family, their roles differ significantly. Choosing between them depends less on print quality and more on volume, consistency, and operational context.

Desktop SLA Printers

Desktop SLA printers are designed to fit into offices, studios, and small labs. These compact resin printers focus on accessibility and manageable footprint. Build volumes are limited, but they are sufficient for dental models, small prototypes, and detailed components. For small batch production, desktop systems provide a balance between quality and convenience.

An SLA 3D printer in this category often emphasizes ease of use and lower upfront cost. While post-processing is still required, workflows are scaled to individual or small-team operation. These machines are commonly used where print frequency is moderate and output volume is predictable.

Industrial SLA Systems

Industrial SLA systems are built for throughput and consistency. Larger build volumes allow multiple parts or sizable components to be produced in a single run. These systems operate in controlled environments, where temperature, lighting, and material handling are tightly managed.

An SLA 3D printer at this scale supports high-volume workflows and standardized output. Print quality remains high, but the emphasis shifts toward reliability and repeatability. Industrial systems are often integrated into broader production pipelines, where resin printing is one step among many.

Desktop vs Industrial SLA Comparison

| Category | Desktop SLA | Industrial SLA |

|---|---|---|

| Build volume | Small–medium | Large |

| Throughput | Low–medium | High |

| Environment | Office / studio | Controlled facility |

SLA vs FDM vs SLS — Key Differences Explained

SLA, FDM, and SLS are often discussed together, but they address different priorities. Each 3D Printer technology is built around distinct material behaviors, energy sources, and output goals. Comparing them clarifies why they coexist rather than replace one another.

Material Differences

An SLA 3D printer uses photopolymer resin, a liquid material that reacts to light. This allows for smooth surfaces and fine features, but requires careful handling and post-processing. Resin properties are tightly linked to optical exposure.

FDM 3D Printer systems rely on thermoplastic filament. The filament is heated, extruded, and cooled into place. This makes FDM versatile and accessible, with a wide range of materials available. However, visible layers and surface texture are inherent to the process.

SLS 3D Printer systems work with polymer powder. Thin layers of powder are spread across a build area and selectively fused. Unfused powder supports the part during printing, enabling complex internal geometry. The trade-off is a grainy surface finish that often requires additional finishing.

Process and Energy Source

Process differences mirror material behavior. An SLA 3D printer uses laser curing or projected light as its energy source. Light determines where material solidifies, while heat plays a minimal role.

FDM relies on extrusion heating. Filament is melted and pushed through a nozzle, then cools to form shape. This mechanical approach is straightforward but limits resolution.

SLS uses powder sintering. Heat from lasers fuses particles together at elevated temperatures. This produces strong parts but introduces thermal complexity and surface texture.

Output Characteristics and Typical Use Cases

These differences translate directly into output. An SLA 3D printer produces smooth surfaces and high geometric clarity, making it suitable for visual models, design validation, and precision prototyping.

FDM produces durable, functional parts suitable for general-purpose fabrication and iterative testing. Surface finish is secondary to strength and convenience.

SLS excels at functional strength and complex geometry, especially in industrial contexts. Parts are often used directly but require finishing for surface refinement.

Final Thought

In the end, SLA 3D printing is less about complexity and more about consistency. The process itself is well defined, the principles are stable, and the strengths of the technology are easy to identify once they are understood. What tends to change over time is not how SLA works, but how it feels to use in real, repeated workflows.

Many technical discussions stop at print quality and process explanation. In practice, day-to-day experience is shaped by quieter factors. Software stability, firmware behavior, and how reliably a printer communicates with its control system often matter just as much as resolution or surface finish. This is where the role of a SLA 3D Printer driver becomes noticeable, acting as the link between digital models and a machine that is expected to perform the same task again and again without surprises.

The same pattern appears when people start talking about the Best SLA Printer. That conversation rarely begins with rankings or specifications. It usually comes after users have a clear sense of what they need—whether that is long-term reliability, predictable output, easier maintenance, or smoother software integration. Without that context, the idea of “best” has very little meaning.

Understanding SLA, then, does not end with knowing how layers are cured or why resin behaves the way it does. It extends into how the technology fits into real workflows, how it is maintained, and how it responds over time. This is where technical knowledge turns into practical judgment.

FAQs About SLA 3D Printer

What is SLA in 3D printing?

SLA stands for stereolithography, a 3D printing method that uses controlled light to cure liquid resin into solid parts. An SLA 3D printer forms objects layer by layer inside a resin vat, focusing on surface quality and fine detail rather than speed.

How accurate is a 3D printer SLA?

Accuracy is one of SLA’s strengths. An SLA 3D printer can reproduce fine features and smooth curves with high dimensional consistency, making it suitable for models that require precise geometry and clean edges.

What are the benefits of SLA 3D printing?

The main benefits include smooth surface finish, high detail resolution, and predictable results. SLA is often chosen when visual quality and shape accuracy matter more than raw strength.

Can I do stereolithography at home?

Yes. Desktop SLA printers make home use possible, though resin handling and post-processing require care and dedicated space.

Why is SLA printing so expensive?

Costs come from resin materials, post-processing steps, and machine precision rather than the printing process alone.