Across logistics hubs, retail floors, office spaces, and industrial sites, labeling has become part of the invisible structure that keeps work moving. Packages move through warehouses because they can be identified instantly. Products sit on shelves with prices and codes that connect them to inventory systems. Files, assets, and samples circulate between departments without confusion because they are clearly marked. In all of these environments, label printers quietly support order without drawing attention to themselves.

What often gets overlooked is that labeling is rarely an isolated task. A shipping label does not exist on its own; it connects physical goods to tracking platforms and delivery networks. A barcode links an item to a database that updates stock levels in real time. In offices, asset labels reduce friction in daily operations, preventing small organizational problems from growing into systemic delays. The real value of label printers sits in this continuity rather than in the printed output alone.

Labels are also designed to live longer than most printed documents. They are scanned repeatedly, exposed to handling, and expected to remain readable throughout a process. Their size, placement, and material are usually dictated by operational needs, not by preference. When labeling breaks down, the impact is immediate—items become harder to trace, workflows slow, and confidence in the system erodes. This is why reliability matters more than appearance in most labeling scenarios.

As workflows become more data-driven, the role of labeling grows more defined. Modern operations rely on standardized identifiers to synchronize physical movement with digital records. In this context, label printers are not accessories. They are tools that help maintain consistency across environments where accuracy and speed are non-negotiable.

Seen this way, labeling functions as part of the infrastructure of modern work. It reinforces structure in environments that depend on clarity and repetition. The printer responsible for producing those labels becomes an extension of the workflow itself, quietly supporting efficiency without demanding attention.

What Are Label Printers?

Label printers are machines designed specifically to produce labels rather than general-purpose documents. Their core purpose is to deliver consistent output on label media, usually in fixed sizes and predictable formats. Unlike multipurpose printers, they assume that every print job serves a functional role, such as identification, tracking, or categorization.

At a structural level, label printers prioritize repeatability and precision. They are optimized for continuous media, roll handling, and materials that standard office printers are not designed to manage. This focus allows labels to align reliably with scanners, databases, and operational systems that depend on exact placement and formatting. The printer’s role is not to offer creative flexibility, but to maintain consistency within a process.

How Label Printers Differ from Regular Printers

The clearest distinction lies in intent. Regular printers are built to handle a wide variety of tasks, from documents to graphics, with flexibility as their main strength. Label printers, by contrast, are purpose-driven. Their hardware, firmware, and media paths are all shaped around producing the same type of output repeatedly and efficiently.

Media handling highlights this difference. Label printers commonly work with rolls instead of sheets, supporting continuous printing and controlled cutting. This makes them suitable for batch operations that would be inefficient on standard printers. Workflow integration also differs. Labels are often generated from databases, inventory tools, or simple input software rather than document editors.

Output expectations further separate the two categories. A document is usually read once and archived or discarded. A label must remain legible, scannable, and correctly positioned throughout its use. Because of this, label printers emphasize reliability over versatility, ensuring that each printed label performs its role within the larger system it supports.

How Label Printers Work?

Behind every printed label, there is a structured flow that connects digital input with physical output. This process is designed to be predictable and repeatable, allowing labeling to fit smoothly into operational systems rather than standing apart from them.

Stage What Happens Role in Workflow Label Design Layout, size, and fields are defined in label design software Ensures consistent format and placement Data Preparation Text, barcodes, or IDs are pulled from manual input or simple databases Connects physical labels to system data Job Processing Software converts the design and data into printer instructions Translates logic into machine-readable commands Printing Execution The printer applies the design onto label media Produces precise, repeatable output Label Application Printed labels are applied to items or packaging Integrates labels into operational flow System Reference Labels are scanned or referenced later Maintains traceability and process continuity

From Label Design to Printed Output

The workflow usually begins at the software level. Label design tools define layout, dimensions, and data fields, ensuring that information appears in consistent positions every time. These designs are often reused, adjusted only when requirements change. For label printers, this consistency is essential because even small shifts in layout can affect scanning accuracy or downstream processing.

Once a design is prepared, data is introduced. This data may come from manual input, spreadsheets, or simple databases, depending on the environment. At this stage, the printer does not yet play an active role. Instead, the system prepares a set of instructions that describe exactly what needs to be printed and how it should appear on the label media.

The printer then interprets these instructions through its internal controller. Unlike general-purpose printing, the output is not treated as a page but as a sequence of labels. Label printers translate the digital layout into precise movements of the print mechanism and media feed, aligning text and barcodes within strict physical boundaries. The result is a label that matches the predefined format without variation.

Finally, the printed label emerges ready for use. In most workflows, it is applied immediately, either by hand or through automated systems. At this point, the label becomes part of a larger operational loop, linking physical items to tracking systems and records. The reliability of label printers lies in their ability to repeat this cycle hundreds or thousands of times without deviation.

Data Input and Printing Workflow

Data handling is a defining part of how labeling systems function. Many labels rely on simple elements such as barcodes, serial numbers, or short text fields. These inputs are often generated dynamically, reflecting real-time changes in inventory, orders, or asset status.

Rather than treating each print job as a standalone task, label printers are typically embedded in lightweight workflows. A barcode may be generated when an item is received, updated when it moves locations, and referenced again during shipping. The printer’s role is to act as a reliable endpoint, converting structured data into a physical identifier at the moment it is needed.

Because of this integration, printing speed and predictability matter more than flexibility. The workflow is optimized to minimize pauses, errors, and manual adjustments. Each printed label reinforces the connection between data and object, allowing systems to remain synchronized as work progresses.

Key Components of a Label Printer

Consistent labeling does not happen by accident. It depends on a set of internal parts that are designed to work together under repetitive conditions.

Component Function Why It Matters Print Mechanism Transfers text and codes onto label surface Determines clarity and consistency Media Path & Feed System Guides label rolls through the printer Maintains alignment during continuous printing Cutter / Tear Bar Separates individual labels Supports efficient batch handling Controller & Firmware Interprets data and manages printer behavior Ensures predictable operation Connectivity Interface Connects printer to computers or networks Enables system integration Software & Driver Layer Translates designs into printer commands Keeps output consistent across platforms

Each element inside a label printer contributes to how reliably it can produce the same result, job after job, without manual adjustment or drift in output.

Print Mechanism

The print mechanism is responsible for transferring information onto the label surface. Depending on the technology used, this may involve a thermal print head or an ink-based system. In both cases, the mechanism is designed for controlled, repetitive motion rather than varied page layouts. For label printers, this focus allows consistent output across long print runs.

Media Path and Feeding System

Labels are commonly supplied on rolls rather than individual sheets. The media path guides this roll through the printer, maintaining alignment and tension as each label is printed. Roll-based feeding supports continuous operation and reduces interruptions. This design choice distinguishes label printers from general printers that are optimized for sheet handling.

Connectivity and Control System

Inside the printer, a controller manages communication between the software input and the hardware components. Firmware interprets commands, coordinates movement, and ensures that data is printed correctly. Connectivity options such as USB, Ethernet, or wireless links allow label printers to fit into different environments without complex configuration.

Software and Driver Layer

The software layer bridges design tools and hardware execution. Drivers translate layouts into instructions the printer can understand, while label design software manages templates and data sources. This layer plays a critical role in maintaining consistency, ensuring that label printers produce predictable results across operating systems and applications.

When these elements are aligned, labeling stops being a fragile step in the process. The printer behaves predictably, output remains stable, and workflows can rely on labels as fixed reference points rather than variables that need constant attention.

Types of Label Printers

Different work environments place very different demands on labeling. What works on a small desk will not survive a warehouse floor, and what suits a personal workspace may slow down a high-volume operation. Because of this, label printers are commonly grouped by how and where they are used rather than by raw technical specifications.

Handheld and Portable Label Makers

Handheld and portable label makers are designed for mobility and simplicity. They are often used in personal, home, or light-duty professional settings where labeling tasks are occasional rather than continuous. These devices usually operate independently, with built-in keyboards or simple mobile app connections that allow users to create labels on the spot.

The strength of this category lies in convenience. Users can label files, cables, shelves, or small containers without setting up a workstation or software environment. Print speeds are modest, media options are limited, and output is typically monochrome. In this context, label printers in portable form trade depth of capability for speed of access and ease of use.

While they are not intended for large batches or system-driven workflows, portable models fill an important role. They support organization at the individual level, where flexibility and immediacy matter more than throughput or integration.

Desktop Label Printers

Desktop label printers occupy the middle ground between personal tools and industrial equipment. They are commonly found in offices, small businesses, retail back rooms, and light warehouse environments. These printers are designed to sit at a workstation and connect to computers or local networks, allowing labels to be generated from software rather than manually entered.

In this category, label printers begin to show their workflow-oriented nature. Media handling improves, print speeds increase, and compatibility with databases or inventory tools becomes more common. Desktop models are often used for shipping labels, product tags, asset tracking, and barcode generation, where consistency and repeatability are essential.

Their limitations are mainly related to scale. While they can handle steady daily use, they are not built for uninterrupted operation over long shifts. For many organizations, however, desktop printers strike a practical balance between capability, size, and cost.

Commercial and Industrial Label Printers

Commercial and industrial label printers are built for volume, durability, and continuous operation. These machines are designed to run for extended periods in demanding environments such as warehouses, manufacturing floors, and logistics centers. Heavy-duty components, reinforced housings, and advanced cooling systems reflect their operational role.

At this level, label printers become deeply embedded in automated or semi-automated workflows. They may be integrated with conveyor systems, scanners, and enterprise software, producing thousands of labels per day without manual intervention. Media options expand to include specialized materials, and print precision remains stable even at high speeds.

The distinction between commercial and industrial models often lies in scale rather than concept. Both prioritize reliability over flexibility, ensuring that labels remain consistent across long production runs. In environments where downtime carries real cost, this category defines what labeling infrastructure looks like in practice.

Across all three types, the classification reflects context of use rather than technological hierarchy. Each form exists because different environments demand different balances between convenience, control, and endurance.

Key Printing Technologies Used in Label Printers

Printing technology defines how labels behave once they leave the printer. Some labels are meant to exist for a few days, others for years. Some need to survive heat, moisture, or friction, while others only need to remain readable during a short shipping cycle. Because of this, label printers rely on several distinct printing technologies, each shaped by different operational priorities rather than visual preference.

Direct Thermal Printing

Direct thermal printing works by applying heat directly to specially coated label material. When the print head heats specific areas, the surface reacts and forms text or barcodes. No ink, toner, or ribbon is involved, which keeps the printing process mechanically simple.

This simplicity makes direct thermal systems efficient for short-term labeling. Shipping labels, temporary identification tags, and transaction-related labels often rely on this method. In workflows where speed and low maintenance matter, label printers using direct thermal technology fit naturally.

The limitation lies in durability. Because the image is formed through heat-sensitive material, labels can fade when exposed to light, heat, or friction. This makes direct thermal printing unsuitable for long-term storage or harsh environments. The technology excels when labels are meant to move quickly through a process rather than remain as permanent identifiers.

Thermal Transfer Printing

Thermal transfer printing introduces a ribbon between the print head and the label surface. Heat from the print head transfers ink from the ribbon onto the label material, creating a more stable and durable image. This added layer increases complexity but also expands the range of usable materials.

For industrial and long-term applications, label printers often rely on thermal transfer technology. Labels produced this way resist fading, moisture, and abrasion far better than direct thermal output. This makes them suitable for inventory storage, asset tracking, and environments where labels must remain legible over time.

The trade-off is operational overhead. Ribbons must be selected, replaced, and matched with compatible media. While this increases consumable costs, it also gives organizations greater control over label performance. Thermal transfer printing is chosen not for convenience, but for reliability under demanding conditions.

Inkjet and Laser Printing for Labels

Inkjet and laser printing technologies are commonly associated with general-purpose printers, but they also appear in labeling contexts when specialized media is used. These systems apply ink or toner onto label sheets rather than rolls, making them familiar to office environments.

In certain scenarios, label printers based on inkjet or laser technology are used for color-rich labels, branding elements, or low-volume production. They offer flexibility in design and color reproduction that thermal methods cannot easily match. However, their reliance on sheet-based media limits efficiency for continuous labeling tasks.

Durability can also vary widely depending on ink, toner, and label material. While acceptable for office or retail settings, inkjet and laser labels are less predictable in industrial workflows. As a result, these technologies are often treated as alternatives rather than primary solutions within labeling systems.

Comparison of Label Printing Technologies

| Technology | Uses | Durability | Consumables |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Thermal | Shipping, receipts | Low–Medium | None |

| Thermal Transfer | Industrial, storage | High | Ribbon |

| Inkjet / Laser | Color labels | Medium | Ink / Toner |

Across these technologies, the choice is rarely about which method is “better.” It is about alignment with workflow expectations. Label printers are selected based on how long labels need to last, where they will be used, and how tightly they must integrate with operational systems. Printing technology becomes a functional decision, not an aesthetic one.

Common Uses of Label Printers

Labeling shows up in many environments, but its role changes depending on context. Sometimes it supports speed, sometimes accuracy, and sometimes compliance. Understanding where and how label printers are used helps clarify why their design emphasizes consistency over versatility.

Shipping and Mailing

In shipping and mailing operations, labels act as carriers of essential information. Addresses, tracking numbers, and barcodes connect packages to logistics networks that rely on rapid scanning and sorting. The label must be readable at every handoff point.

Here, label printers support throughput and reliability. Labels are often generated dynamically as orders are processed, printed in high volumes, and applied immediately. The focus is not on appearance, but on accuracy and scan performance under time pressure.

Office and Home Organization

In office and home environments, labeling supports clarity and organization. Files, folders, cables, storage boxes, and equipment benefit from consistent identification, especially as shared spaces become more complex.

Within this context, label printers are used less frequently but still serve an important role. They reduce small inefficiencies that accumulate over time, helping individuals maintain order without relying on memory or ad hoc systems. The emphasis is ease of use rather than scale.

Retail and Point-of-Sale

Retail environments rely on labels to bridge physical products and pricing systems. Shelf labels, product tags, and barcode stickers ensure that inventory, pricing, and checkout systems remain synchronized.

For retail operations, label printers provide a way to update information quickly without disrupting floor operations. Labels must be consistent, legible, and easy to replace as products change. Speed and integration with point-of-sale systems are more important than long-term durability.

Industrial and Warehouse Operations

In industrial and warehouse settings, labeling becomes part of the infrastructure. Inventory movement, storage location tracking, and process control all depend on reliable identification.

Here, label printers operate continuously, often producing labels that must survive harsh conditions. Heat, dust, moisture, and handling are expected, not exceptional. The printer’s role is to maintain stability in environments where errors carry operational cost.

Healthcare and Laboratory Environments

Healthcare and laboratory settings place unique demands on labeling. Samples, patient records, medications, and equipment all require precise identification to prevent errors.

In these environments, label printers support safety and compliance. Labels must remain legible, resistant to chemicals or refrigeration, and consistently formatted. The printer becomes part of a controlled system where accuracy is not optional.

At scale, these varied use cases explain why labeling continues to expand across industries. According to Fortune Business Insights, the global label printer market continues to expand due to rising demand across logistics, healthcare, and retail sectors, driven by the need for reliable and efficient labeling systems.

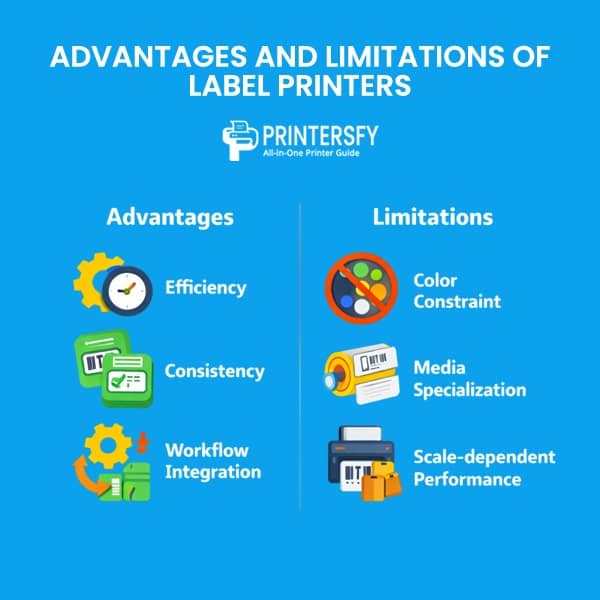

Advantages and Limitations of Label Printers

Labeling tools are often judged by output quality alone, but their real value appears when viewed inside a working system. In many environments, label printers are chosen not because they are versatile, but because they are predictable. That predictability brings clear advantages, while also introducing limitations that matter once scale, variety, or visual demands increase.

Key Advantages

The strongest benefits of labeling systems emerge in operational settings where repetition and accuracy are critical. Rather than adapting to every task, these devices reinforce consistency across processes.

- Efficiency: Label printers are designed for fast, repeatable output. Once a format is defined, labels can be generated with minimal setup, reducing manual effort and turnaround time. This efficiency becomes especially visible in shipping, inventory handling, and administrative workflows where delays compound quickly.

- Consistency: Every label follows the same layout, spacing, and alignment. This consistency ensures reliable scanning, easier verification, and fewer errors across teams. In system-driven environments, label printers reduce variation that would otherwise introduce friction or misreads.

- Workflow integration: Labels often connect physical items to digital systems. When integrated properly, label printers act as endpoints within larger workflows, translating data directly into usable identifiers. This integration supports traceability, accountability, and process continuity without adding complexity.

Together, these advantages explain why labeling devices remain common in logistics, retail, healthcare, and industrial operations. The goal is not flexibility, but stability.

Practical Limitations

Despite their strengths, labeling tools are not universal solutions. Their focus on repetition and control naturally limits their range of use.

- Color and visual constraints: Many labeling systems prioritize monochrome output. While this supports clarity and durability, it limits design flexibility. For branding-heavy or visually rich applications, label printers may feel restrictive compared to general-purpose printing options.

- Media specialization: Label printers are optimized for specific media types, such as rolls or predefined materials. This specialization improves reliability but reduces adaptability. Switching between uncommon sizes or materials can require hardware adjustments or different models.

- Scale-specific performance: Not all label printers perform equally across scales. Devices designed for desktop use may struggle under continuous workloads, while industrial models can be excessive for light-duty environments. Choosing the wrong scale introduces inefficiency rather than solving it.

Key Features to Consider in a Label Printer

Choosing a labeling device is rarely about finding the most advanced option. It is about finding a tool that fits the way work actually happens. Features matter not in isolation, but in how they support daily routines, volumes, and constraints. In practical terms, label printers succeed when their capabilities align with workflow expectations rather than exceeding them.

Connectivity Options

Connectivity determines how easily a printer fits into an existing setup. USB connections suit single workstations, while Ethernet allows shared access across teams. Wireless options such as Wi-Fi or Bluetooth support flexible placement and mobile workflows. The right choice depends less on novelty and more on how labels are generated and where printing needs to occur.

Media Handling and Compatibility

Label size, material, and format shape how output is used. Printers designed for roll media support continuous printing and higher efficiency, while limited media compatibility can become a bottleneck over time. In this area, label printers are judged by how reliably they handle specific materials rather than by how many formats they claim to support.

Print Quality and Speed

Resolution and speed exist in tension. Higher resolution improves clarity for small text and dense barcodes, while faster output supports throughput in busy environments. The practical balance depends on whether labels are scanned quickly or inspected closely. Over-optimizing either side often leads to unnecessary trade-offs.

Durability and Build Quality

Office environments place different demands on hardware than warehouses or factory floors. Lightweight construction may suit desk use, but sustained operation requires reinforced components. Build quality becomes a long-term consideration once printing shifts from occasional to continuous.

Software, Drivers, and Integration

Ease of use often comes down to software. Drivers must work reliably across operating systems, while design tools should support templates and basic data input without friction. For label printers, stable integration matters more than feature-rich interfaces that slow down routine tasks.

Operating Cost Considerations

Beyond the device itself, consumables define long-term cost. Media types, ribbon usage, and replacement cycles affect total ownership expense. A lower upfront price can be offset quickly by inefficient consumption patterns if they do not match usage volume.

Key Features to Evaluate in a Label Printer

| Feature | Why It Matters |

|---|---|

| Connectivity | Supports workflow integration |

| Media Compatibility | Allows label flexibility |

| Print Speed | Affects operational efficiency |

| Durability | Supports long-term reliability |

| Software | Simplifies label design |

The Role of Label Printers in Modern Business and Operations

As businesses grow more interconnected, operational efficiency is no longer defined by speed alone. It depends on how reliably information moves alongside physical goods, documents, and assets. In this context, label printers support visibility across systems that would otherwise rely on manual checks or fragmented records. Their role is subtle, but foundational.

Labeling as Part of System Efficiency

Labeling works best when it removes ambiguity rather than adding steps. A clear identifier allows systems to confirm location, status, and ownership without interruption. This is where labeling becomes part of system efficiency rather than a standalone task. When identifiers are standardized, scanning replaces interpretation, and processes move forward with fewer decision points.

Within daily operations, label printers contribute to this efficiency by producing output that systems can depend on. The value does not come from novelty or advanced features, but from predictability. Labels appear where they are expected, carry the information they should, and behave consistently across environments. That reliability reduces friction in workflows that repeat thousands of times.

Scalability and Process Standardization

As operations scale, informal methods begin to fail. What works for a small team becomes unreliable once volumes increase or responsibilities spread across departments. Standardization becomes necessary, and labeling plays a central role in enforcing it. Consistent identifiers allow processes to scale without constant retraining or manual oversight.

At this level, label printers function as stabilizing tools. They help organizations maintain process integrity as complexity increases, ensuring that growth does not erode clarity. This explains why labeling continues to expand across sectors. According to FESPA, global label printing market value is projected to reach approximately USD 58.8 billion by 2027, reflecting sustained demand for labeling solutions across multiple industries worldwide.

Related Specialized Printers and How They Differ from Label Printers

Not every printer that produces small formats or uses thermal technology is intended for labeling. This section exists to clarify common overlaps and prevent functional confusion, especially in environments where multiple printer types coexist. While label printers are optimized for precision and system integration, other specialized printers serve distinct purposes.

Large-Format and Visual Output Printers

Large-format printers, including plotters and photo printers, are built around visual output and size. Their primary goal is to reproduce images, graphics, or designs at scales far beyond standard documents. Media width, color accuracy, and resolution take priority over alignment and repetition.

Although these printers can technically print on adhesive media, they are not substitutes for label printers. The focus is visual impact rather than operational precision. A banner printer or poster is meant to be seen, not scanned repeatedly or tracked through a system. Using large-format devices for labeling tasks often introduces inefficiency rather than solving it.

Thermal and Transaction Printers

Thermal printers are frequently associated with labeling, but not all thermal devices serve the same role. Receipt printer and transaction printers, for example, are optimized for speed and cost in point-of-sale environments. Their output is designed to be short-lived, often fading over time.

In contrast, label printers use thermal technology with different expectations. Labels are meant to persist, remain legible, and integrate with tracking systems. The difference lies less in the printing method and more in the intended lifecycle of the output. Receipts document a moment; labels support a process.

Size-Specific and Material-Specific Printers

Some printers are defined primarily by the media they handle rather than the tasks they support. A3 printers or A2 printers focus on larger sheet sizes, while textile printers are built to apply ink to fabric surfaces. These devices solve specific production problems but operate outside typical labeling workflows.

Even when adhesive media is involved, the goals differ. Material-specific printers emphasize surface compatibility or visual durability, not standardized formatting or data integration. This is where label printers remain distinct, prioritizing consistency and system alignment over material experimentation.

Final Thoughts

Labeling rarely draws attention when it works well. Its success is measured by the absence of confusion rather than by visible impact. In many work environments, labels quietly hold systems together, linking physical items to information without demanding oversight.

When viewed this way, label printers are not productivity shortcuts or temporary solutions. They are tools that support order over time, reinforcing structure in workflows that depend on accuracy and repetition. Their value becomes clearer as operations mature and informal methods give way to standardized processes.

Rather than chasing trends or features, effective labeling focuses on fit. The right device is the one that aligns with how work actually happens, not how it is imagined. In that sense, label printers earn their place by staying consistent, dependable, and largely unnoticed—doing their job so the rest of the system can do its own.

FAQs About Label Printers

Do I need a special printer to print labels?

Not always. Standard printers can print on label sheets, but they are not optimized for repeated labeling tasks or roll-based media.

What kind of printer is best for printing labels?

The best option depends on volume and purpose. Dedicated label printers are better for frequent, consistent labeling, while general printers suit occasional needs.

Is it worth getting a label printer?

For regular shipping, inventory, or organization tasks, a label printer is usually worth it because it saves time and reduces manual errors.

Is it cheaper to print your own labels or buy them?

Printing your own labels is often cheaper in the long run, especially at scale, since you control materials and avoid outsourcing costs.

What type of printer is best for labels?

For high-volume or system-driven workflows, label printers are the most reliable choice due to their consistency, speed, and workflow integration.