In recent years, a 3D printer has become a familiar presence across many fields. It appears in schools, workshops, research labs, and small businesses. The term feels established, yet the technology behind it is often taken for granted rather than examined.

Discussions around 3D printing technology usually focus on results instead of process. Objects appear quickly, designs become tangible, and production feels almost automatic. Because of this, the underlying shift in manufacturing logic is easy to overlook.

Digital fabrication changes where production begins. Instead of starting with tools or molds, everything starts as a digital model. Decisions about shape, structure, and tolerance are made on a screen. The physical object only reflects those earlier choices.

This approach aligns closely with additive manufacturing. Material is built up in controlled steps rather than carved away. The difference sounds simple, but its impact is not. Designs no longer need to conform to traditional tooling limits. Complexity becomes more accessible.

At first, these changes may feel abstract. The machine works, the object prints, and the outcome seems sufficient. Over time, patterns emerge. Revisions take minutes instead of weeks. Design experiments become routine rather than risky.

As access widens, the technology moves into everyday environments. Classrooms use it to connect theory with practice. Small teams rely on it to test ideas without outside suppliers. Individuals use it to create solutions for specific needs.

Seen in this light, the relevance becomes clearer. The technology reshapes how ideas become objects. It alters who participates in making things. It also changes the pace at which experimentation and refinement can happen.

What Is a 3D Printer?

The phrase what is a 3D printer often invites a comparison rather than a simple definition. Most people understand manufacturing through familiar processes like cutting, drilling, or molding. In those methods, production begins with raw material and removes portions until the desired shape appears.

A 3D printer follows a different logic. The object does not emerge from subtraction, but from accumulation. Material is placed only where the design requires it. Nothing is carved away to reveal form. The shape grows instead of being uncovered.

This difference places additive manufacturing in contrast with subtractive manufacturing. Traditional methods demand tools that can physically reach every surface. Designs must accommodate cutting paths, molds, or dies. These constraints influence form long before production begins.

With a 3D printer, those limitations soften. Internal structures can exist without access points. Complex geometry does not automatically increase tooling cost. The design phase carries more freedom, while the production phase becomes more predictable.

Another distinction appears in preparation. Traditional manufacturing often requires custom tooling before production starts. That setup can take weeks and carries financial risk. Additive workflows rely primarily on digital files. A design change may only require a software adjustment.

The definition of 3D printer also reflects this shift toward digital control. Once the file is ready, the machine follows instructions precisely. Movement, temperature, and material flow are all governed by code. Physical intervention is minimal once printing begins.

For many users, this difference changes expectations. Manufacturing feels less distant and less permanent. Iteration becomes part of the process rather than a costly exception. In that sense, a 3D printer is not just a tool, but a different way of approaching production itself.

History and Evolution of 3D Printing

Early Development of 3D Printing

The history of 3D printing did not begin with consumer machines or desktop tools. It emerged quietly inside industrial research environments. Engineers were searching for faster ways to test designs without committing to full production.

Early systems focused on prototyping rather than final products. Speed mattered more than appearance. Accuracy mattered more than surface finish. These machines allowed engineers to evaluate form and fit before investing in tooling.

At the time, the technology was expensive and highly specialized. Operation required trained technicians. Materials were limited in variety and performance. Printing times were slow by modern standards. Despite these limitations, the advantage was clear.

Design feedback cycles shortened dramatically. Engineers could hold a physical model within days. Mistakes became visible earlier in development. This reduced costly revisions later in the process. The value of layer-based fabrication became difficult to ignore.

Evolution from Industrial to Consumer 3D Printers

The evolution of 3D printers accelerated as supporting technologies improved. Electronics became smaller and cheaper. Software tools grew more capable and user friendly. Hardware designs became easier to replicate and refine.

Open-source communities played an important role during this phase. Shared designs lowered barriers to entry. Experimentation moved beyond corporate labs. Knowledge spread through forums, documentation, and user groups.

Gradually, machines began appearing outside industrial settings. Schools adopted them for design education. Hobbyists explored personal projects. Small businesses used them for rapid iteration and customization.

These early consumer machines lacked industrial precision. Reliability varied widely. Still, they proved that the technology could exist beyond specialized environments. Accessibility mattered more than perfection.

Over time, the gap between industrial and consumer systems narrowed. Materials improved. Motion systems became more accurate. Software simplified complex workflows. What once required expert oversight became manageable for non-specialists.

Today, the evolution of 3D printing continues in parallel directions. Industrial systems push toward performance and scale. Consumer machines focus on reliability and ease of use. Together, they reflect a technology shaped by both engineering demand and widespread curiosity.

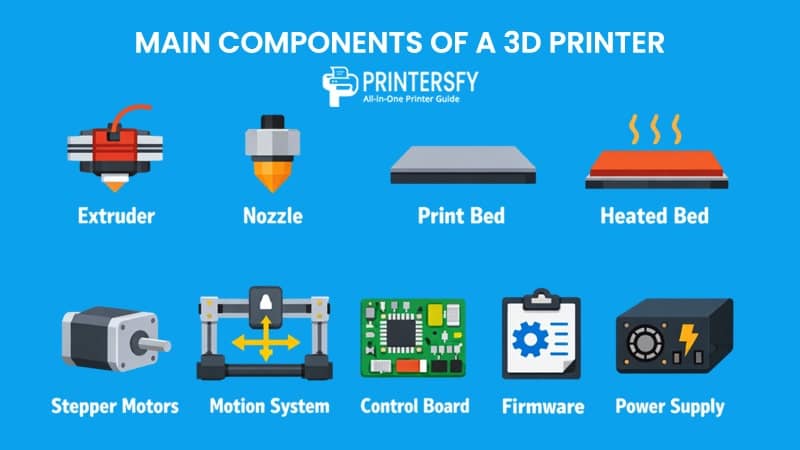

Main Components of a 3D Printer and Their Functions

When people talk about print quality, they often focus on settings or materials. The hardware itself receives less attention. In reality, the behavior of a 3D printer is shaped primarily by its physical components. Every successful print reflects how well these parts operate together.

The main 3D printer components are designed to manage three things at once: material flow, controlled movement, and stable temperature. If one of these elements drifts out of balance, problems appear quickly. Layer shifts, poor adhesion, or uneven surfaces rarely come from software alone.

Looking closely at the parts of a 3D printer also explains why two machines with similar specifications can behave very differently. Build quality, tolerances, and component interaction matter more than raw numbers on a product page. This is where reliability is decided.

Core Hardware Components

Although designs vary, most machines rely on the same core structure. These elements form the mechanical and electronic backbone of the system. Their job is not to impress visually, but to remain consistent over long print sessions.

Component Function Impact Extruder Grips and feeds filament at a controlled rate into the hot end Determines extrusion consistency and layer strength Nozzle Shapes and deposits molten material onto the print surface Affects surface detail, print resolution, and print speed Print Bed (Build Plate) Supports the object during printing and anchors the first layer Influences bed adhesion, warping, and print success Heated Bed Maintains controlled surface temperature during printing Reduces warping and improves layer bonding Stepper Motors Drive precise movement along each axis Defines positional accuracy and dimensional consistency Motion System (Belts / Rails / Lead Screws) Transfers motor movement to the print head or bed Affects smoothness, vibration, and repeatability Control Board Interprets instructions and coordinates machine behavior Governs timing, motion accuracy, and system stability Firmware Defines how commands are executed and limited Impacts reliability, safety, and motion behavior Power Supply Delivers stable electrical power to all components Prevents print interruptions and component failure

Each printer component supports the others. Movement depends on stable electronics. Material flow depends on accurate heating. Adhesion depends on temperature and positioning. The system only performs well when these relationships remain steady.

Extruder and Nozzle

The extruder controls how material enters the printing process. It grips filament and pushes it forward at a controlled rate. Consistency here matters more than speed. Uneven feeding leads to weak layers and visible defects.

At the end of this path sits the nozzle. It shapes how material exits the system. Nozzle diameter affects detail, surface texture, and print time. Smaller nozzles allow finer features. Larger nozzles prioritize strength and speed.

The extruder and nozzle work as a single unit. Pressure, temperature, and movement must align. If one element falls out of sync, extrusion becomes unreliable. Many print issues trace back to this relationship.

Maintenance also plays a role. Residue buildup inside the nozzle restricts flow. Worn extruder gears reduce grip. Regular inspection keeps material delivery predictable.

Print Bed (Build Plate)

The print bed provides the foundation for every object. Its role seems simple, yet it influences nearly every stage of printing. A stable first layer determines whether a print succeeds or fails.

Bed leveling ensures consistent distance between nozzle and surface. Even slight variation causes uneven adhesion. Too much distance leads to poor bonding. Too little causes material buildup or nozzle damage.

Many systems include a heated bed. Heat improves adhesion and reduces warping during cooling. Different materials respond to different temperatures. Incorrect settings often cause corners to lift or layers to separate.

Surface material also matters. Glass, textured metal, and coated plates behave differently. Cleanliness affects adhesion more than most users expect. Oils and dust interfere with bonding.

Stepper Motors

Stepper motors control movement along each axis. They translate digital instructions into precise mechanical motion. Accuracy depends on both motor quality and mechanical setup.

Each movement must repeat consistently across thousands of layers. Missed steps create visible shifts. Poor belt tension introduces vibration. Mechanical slack reduces dimensional accuracy.

Motors operate in coordination with rails, belts, or lead screws. Smooth motion requires proper alignment. Noise or vibration often signals mechanical resistance or misconfiguration.

Reliable motors allow predictable behavior. They ensure each layer aligns with the previous one. Precision here defines the overall geometry of printed parts.

Control Board and Power Supply

The control board acts as the machine’s coordinator. It processes instructions and manages timing. Every movement, temperature change, and fan adjustment originates here.

Firmware determines how the board interprets commands. Limits, acceleration, and safety features are defined in code. Updates often improve stability rather than raw performance.

The power supply provides consistent electrical flow. Voltage instability affects heaters and motors. Sudden drops can interrupt prints or damage components. Safety systems rely on steady power delivery.

Together, these electronics keep the machine predictable. When they fail, behavior becomes erratic. Stable electronics are essential for long prints and unattended operation.

How Does a 3D Printer Work? Step-by-Step

Descriptions of printing often jump straight to results. Objects appear layer by layer, and the process feels automatic. Looking closer at how a 3D printer works reveals a structured sequence where each stage depends on the previous one.

The 3D printing process begins long before material is heated. Decisions made early shape everything that follows. Errors introduced upstream rarely disappear later.

Creating a 3D Model

Every print starts as a digital model. This file defines shape, scale, and structure. It does not describe how to print, only what the final object should be.

Design choices matter more than beginners expect. Thin walls may print poorly. Unsupported overhangs may fail. Internal geometry affects strength and material use.

Models can be created from scratch or sourced from libraries. Either way, they must be printable. Gaps, intersecting surfaces, or non-manifold geometry cause issues later.

This stage sets expectations. A clean model reduces guesswork downstream. Many failed prints begin with flawed digital designs.

Slicing the Model

Slicing translates the model into instructions the machine can follow. Software divides the object into layers and calculates movement paths. This step defines layer height, speed, and temperature.

Slicing also controls internal structure. Infill patterns affect strength and weight. Wall thickness affects durability. Support structures are added where needed.

This stage bridges design and fabrication. Small adjustments have visible effects. Faster speeds trade detail for time. Lower temperatures affect bonding.

The output is a machine-readable file. It dictates every action during printing. Once slicing is complete, the process becomes mechanical.

Printing Layer by Layer

Printing begins with heating material and preparing the bed. The first layer sets the tone. Adhesion and alignment matter immediately.

Material is deposited according to instructions. Each layer bonds to the one beneath it. This is the essence of layer-by-layer printing.

Movement follows precise coordinates. Motors guide the print head smoothly. Cooling fans manage temperature to prevent deformation.

Consistency matters more than speed. Interruptions leave marks. Environmental changes affect results. Successful prints rely on stable conditions.

Watching this stage reveals the logic of additive manufacturing. Shapes emerge gradually. Errors compound if unnoticed. Patience improves outcomes.

Cooling and Post-Processing

When printing ends, the object is not truly finished. Cooling begins immediately. Uneven cooling introduces stress. Controlled conditions preserve shape.

Once removed, parts may require cleanup. Supports are detached carefully. Surface finishing improves appearance. Some materials need additional curing or treatment.

Post-processing reveals the consequences of earlier decisions. Weak layers reflect poor bonding. Rough surfaces reflect speed or cooling choices.

This final stage closes the loop. The physical result mirrors the entire workflow. Every decision leaves a trace.

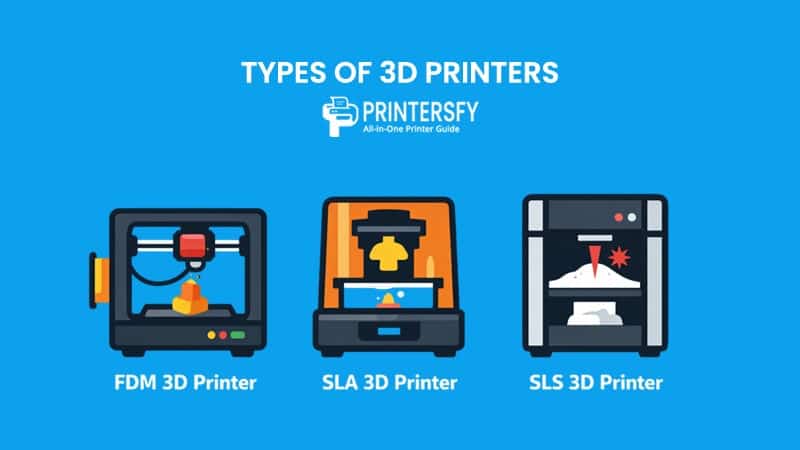

Types of 3D Printers

As interest grows, the variety of machines becomes harder to ignore. The market no longer revolves around a single approach. Instead, several distinct technologies coexist, each shaped by different priorities. This diversity explains why conversations about these types of printers often feel confusing at first.

At a glance, many machines appear similar. They all turn digital files into physical objects. The differences emerge in how material is handled, how layers are formed, and what kind of results can be expected. Accuracy, surface quality, and workflow vary more than beginners usually anticipate.

The most common distinction separates filament-based and resin-based systems. Industrial machines extend beyond these categories. Powder-based technologies introduce another layer of complexity. Together, they form the backbone of the modern 3D printer landscape.

FDM 3D Printers

FDM machines are the most familiar option for many users. They rely on solid thermoplastic filament. This filament is heated, softened, and pushed through a nozzle. The material is deposited layer by layer until the object takes shape.

This approach dominates home and educational environments. Entry costs are relatively low. Materials are widely available. Maintenance is manageable without specialized equipment. These factors explain why many first-time users encounter this technology first.

Surface finish is one of the main trade-offs. Layer lines are usually visible. Fine detail depends heavily on calibration and settings. Slower print speeds improve appearance, but increase production time.

Material choice plays a large role in outcomes. Rigid plastics, flexible filaments, and composites are all possible. Switching materials is straightforward, though each requires tuning. This versatility supports experimentation and learning.

For functional parts, FDM systems offer acceptable strength. Orientation affects durability. Layers bond less strongly in one direction. Users often adjust designs to compensate.

In everyday use, FDM machines feel forgiving. Failed prints waste time and material, but costs remain manageable. This makes them suitable for prototyping and iteration. Many users rely on them as a practical starting point.

SLA 3D Printers

SLA machines approach printing from a different angle. Instead of solid filament, they use liquid resin. Light exposure cures the resin, hardening it into solid layers. The result is a fundamentally different surface quality.

Prints produced this way appear smooth and detailed. Small features reproduce accurately. Curved surfaces lack the stepped appearance common in filament prints. This visual difference often defines first impressions.

Workflow complexity increases with this technology. Resin handling requires care. Post-print washing and curing are necessary. Protective equipment is recommended. These steps add time and responsibility.

Material behavior also differs. Resin formulations vary widely. Some focus on visual quality. Others emphasize strength or flexibility. Choosing the right resin affects performance and longevity.

SLA systems are common in professional settings. Dental labs rely on accuracy. Jewelry designers value fine detail. Model makers appreciate surface finish. Precision often outweighs convenience.

When comparing FDM vs SLA, priorities become clear. Filament systems favor simplicity. Resin systems favor resolution. The choice reflects how much effort users are willing to invest after printing ends.

DLP and SLS 3D Printers

DLP machines share similarities with SLA systems. Both rely on liquid resin. The difference lies in how light is applied. DLP exposes entire layers at once instead of tracing them.

This method improves speed. Print times depend less on object complexity. Layer consistency remains high. Small batch production becomes more efficient.

SLS systems operate in a completely different way. They use powdered material rather than filament or resin. A laser selectively fuses powder particles. Unfused powder supports the object naturally.

This eliminates the need for support structures. Complex shapes print without extra preparation. Internal channels and moving parts are possible. Design freedom increases significantly.

Parts produced through SLS are strong and functional. Materials such as nylon offer good mechanical properties. Surface finish is slightly textured. Post-processing focuses on cleaning rather than curing.

Cost and complexity limit accessibility. These machines are expensive. Operation requires controlled environments. Training is often necessary. As a result, usage remains industrial.

DLP and SLS technologies serve specialized roles. They address needs that consumer machines cannot. Performance justifies investment in professional workflows.

Comparison of Common 3D Printer Types

Choosing between these technologies depends on context. Budget, accuracy, and workflow all matter. Resin vs filament printers differ not only in output, but in daily operation.

Filament systems emphasize accessibility and adaptability. Resin systems emphasize detail and precision. Powder-based systems emphasize strength and complexity. Each category fills a specific niche.

Production volume also influences decisions. Prototypes and education favor filament machines. Detailed models favor resin. End-use parts favor powder systems.

These differences explain why no single machine replaces all others. The 3D printer ecosystem grows by specialization rather than convergence.

Type Material Accuracy Typical Use FDM 3D Printer Filament Medium Home & education SLA 3D Printer Resin High Dental & jewelry SLS 3D Printer Powder Very High Industrial

Materials Used in 3D Printing

Material selection influences nearly every aspect of printing. Strength, flexibility, surface finish, and durability all depend on what is used. This is why discussions about 3D printing materials often matter more than machine specifications.

Modern systems support a growing range of options. Some materials prioritize ease of use. Others focus on performance under stress. Temperature tolerance, chemical resistance, and finish vary widely.

Material behavior also affects reliability. Warping, adhesion, and layer bonding depend on composition. Matching material to application reduces frustration and waste.

Filament Materials

Filament materials are used primarily in extrusion-based systems. They are supplied as spools of solid plastic. Heating softens the filament for deposition. Cooling solidifies each layer.

Different filaments behave differently during printing. Flow characteristics vary. Temperature windows matter. Print speed influences bonding. Small adjustments produce noticeable changes.

Choosing the right 3D printer filament often determines success. Improper selection leads to weak parts or failed prints. Experience helps identify patterns.

PLA

PLA is widely used for general printing. It melts at relatively low temperatures. Adhesion is usually reliable. Warping is minimal under normal conditions.

Printed parts are rigid and dimensionally stable. Heat resistance is limited. Prolonged exposure to warmth causes deformation. Indoor use is preferred.

PLA suits prototypes and visual models. Educational settings favor it. Ease of printing explains its popularity.

ABS

ABS offers improved strength and heat resistance. Printing requires higher temperatures. A heated bed is essential. Enclosures reduce warping.

Odor is noticeable during printing. Ventilation improves comfort. Layer adhesion is strong when settings are correct. Surface finishing is possible with solvents.

PLA vs ABS comparisons highlight trade-offs. PLA prints easily. ABS performs better under stress. Application determines suitability.

PETG

PETG combines durability with easier handling. It resists moisture and chemicals. Warping is less severe than ABS. Layer bonding is strong.

Surface finish appears smoother than ABS. Transparency is possible. PETG suits functional parts and containers. Many users see it as a middle ground.

Printing temperatures remain moderate. Calibration is forgiving. This balance explains growing adoption.

TPU

TPU is flexible and elastic. It bends without breaking. Printing requires slower speeds. Extruder design affects results.

Parts absorb impact and vibration. Seals, grips, and protective elements are common uses. Dimensional accuracy requires careful tuning.

Flexible filaments expand design possibilities. They introduce challenges, but reward patience.

Resin Materials

Resin materials are used in light-based systems. They begin as liquid polymers. Light exposure cures them into solid layers. Properties depend on formulation.

Standard resins emphasize detail and smooth finish. Engineering resins improve strength and heat resistance. Flexible resins allow controlled deformation.

Post-processing is mandatory. Washing removes uncured resin. Additional curing improves durability. Safety procedures matter during handling.

Material cost is higher than filament. Waste management is necessary. Output quality often justifies the effort.

The range of materials continues to expand. New blends address specific needs. This growth broadens application potential for every 3D printer system.

Material choice ultimately defines performance. Machines provide capability. Materials decide results.

Applications and Uses of 3D Printers

As the technology matures, its role becomes easier to recognize in everyday contexts. A 3D printer no longer sits only in experimental labs. It appears in classrooms, production floors, clinics, and small studios. Each environment uses the same core capability in different ways.

What changes is not the machine, but the intention behind it. In some settings, speed matters most. In others, accuracy or customization takes priority. These differences explain why adoption continues across unrelated fields.

Education

In education, printing supports learning through making. Abstract ideas become tangible. Students see how digital decisions affect physical results. This connection changes how design and engineering concepts are understood.

Teachers use printing to introduce problem-solving. A design flaw becomes visible instead of theoretical. Iteration feels natural rather than punitive. Mistakes turn into feedback rather than failure.

Beyond engineering, the technology reaches art, architecture, and science classes. Models support visualization. Projects feel grounded in real outcomes. Engagement often increases when students create something physical.

For institutions, cost and accessibility matter. Entry-level machines meet most educational needs. Reliability outweighs extreme precision. The value lies in process rather than perfection.

Manufacturing and Industry

In industrial settings, a 3D printer supports speed and flexibility. Prototypes are produced internally instead of outsourced. Engineers test form, fit, and function early. Development cycles shorten noticeably.

Small batch production also becomes practical. Custom fixtures, jigs, and replacement parts are printed on demand. Downtime decreases. Inventory requirements shrink.

In some cases, printed parts move beyond testing. End-use components appear in tooling and specialized equipment. Material choice determines suitability. Performance requirements guide adoption.

This flexibility explains why adoption continues to rise. According to Fortune Business Insights, the global 3D printing market was valued at USD 19.33 billion in 2024 and is projected to exceed USD 101 billion by 2032, indicating rapid adoption across industries.

Medical Applications

Medical use highlights the value of customization. Patient-specific solutions become possible. Anatomical models support surgical planning. Doctors visualize complex structures before procedures.

Dental and orthodontic fields rely heavily on precision. Custom aligners, crowns, and guides are produced routinely. Accuracy and repeatability matter more than speed.

Prosthetics represent another application. Printed components reduce cost and lead time. Adjustments happen quickly. Comfort improves through iteration.

Regulation and material safety shape this space. Validation matters. Despite constraints, growth continues where benefits outweigh complexity.

Small Businesses and Hobbyists

For small businesses, printing lowers barriers to entry. Product ideas move from concept to prototype quickly. External manufacturing becomes optional. Control stays in-house.

Customization becomes a selling point. Short production runs feel viable. Feedback loops shorten. Products evolve based on real use rather than assumptions.

Hobbyists use printing for exploration and problem-solving. Replacement parts, tools, and personal projects are common. The machine becomes a practical household tool rather than a novelty.

Across these uses, the 3D printer acts less like a factory and more like a bridge. It connects ideas to outcomes with fewer intermediaries.

Advantages and Limitations of 3D Printing

Discussions often frame the technology as transformative. In practice, benefits and constraints exist side by side. Understanding both prevents unrealistic expectations and disappointment.

Advantages

One advantage of 3D printing lies in speed. Designs move quickly from digital to physical form. Iteration becomes part of the workflow rather than a delay.

Customization also stands out. Unique parts require no special tooling. Variation does not automatically increase cost. This suits specialized or low-volume needs.

Material efficiency matters as well. Additive processes place material only where needed. Waste is reduced compared to subtractive methods. This efficiency supports sustainable practices.

Decentralized production offers another benefit. Parts are produced close to use. Shipping and storage demands decrease. Responsiveness improves.

Limitations

The limitations of 3D printers become clear with scale. Large production volumes favor traditional manufacturing. Print speed cannot always compete.

Material properties also impose constraints. Layer bonding varies by orientation. Strength may differ from molded parts. Application suitability depends on these factors.

Surface finish and accuracy require trade-offs. Fine detail often increases print time. Post-processing adds effort. Expectations must align with capability.

Cost can also mislead. Entry machines appear affordable. Materials, maintenance, and time accumulate. Value depends on consistent use.

Recognizing both sides leads to better decisions. The advantages of 3D printing shine when applied thoughtfully. Limitations define where alternatives remain relevant.

Software Used in 3D Printing

Hardware attracts attention, but software shapes results. Without proper software, even capable machines perform poorly. The workflow depends on digital tools at every stage.

3D Design Software

Design software defines the object itself. Geometry, dimensions, and structure originate here. Decisions made at this stage affect everything downstream.

Different tools suit different users. Engineers prefer parametric control. Artists favor sculpting interfaces. Ease of modification matters more than visual polish.

Design software also influences printability. Wall thickness, overhangs, and internal structures must respect physical constraints. Good design reduces trial and error.

Slicing Software

Slicing software bridges design and fabrication. It converts geometry into instructions. Layer height, speed, and temperature are defined here.

This stage controls internal structure. Infill density affects strength. Support placement affects surface quality. Small changes produce visible differences.

Reliable slicing software improves consistency. Profiles reduce setup time. Updates often improve performance rather than features.

Together, design and slicing tools form the core of 3D printer software. Hardware executes instructions. Software decides what those instructions become.

How to Choose a 3D Printer for Beginners

For newcomers, the idea of buying a first machine often feels more complicated than it should. Product listings emphasize specifications, brand names, and features that appear equally important. Without context, it becomes difficult to tell what actually matters and what can be ignored.

Choosing a 3D printer is less about chasing the most advanced option and more about matching the machine to realistic expectations. Beginners benefit most from stability, predictability, and a gentle learning curve. Early success builds confidence faster than impressive specifications ever could.

Intended Use

The first question is not technical. It is practical. What do you want to make, and why? A beginner 3D printer used for school projects has different requirements than one used for functional parts or creative models.

Some users focus on learning design basics. Others want to prototype small products. Some simply want a tool to fix household problems. Each goal pushes priorities in a different direction.

Print size matters here. Large build volumes sound appealing, but they add complexity. Small and medium prints cover most beginner needs. Reliability matters more than scale.

Accuracy also depends on purpose. Decorative objects tolerate imperfections. Functional parts demand consistency. Defining use early prevents disappointment later.

Budget

Budget shapes every decision, whether acknowledged or not. Entry-level machines appear affordable at first glance. However, price alone does not define value.

Cheaper machines often require more manual adjustment. They may work well, but demand patience. Beginners with limited time may find this frustrating. Paying slightly more often buys stability rather than raw performance.

It helps to separate initial cost from long-term expense. Accessories, replacement parts, and materials add up. A realistic budget includes these ongoing needs.

Setting a firm spending range narrows options quickly. This reduces overwhelm. It also prevents impulse upgrades that add little real benefit.

Ease of Use

Ease of use matters more than beginners expect. Early experiences shape long-term interest. A machine that constantly needs adjustment discourages learning.

Features that simplify setup make a difference. Automatic bed leveling reduces frustration. Clear interfaces reduce mistakes. Preconfigured profiles shorten setup time.

Community support also affects ease of use. Popular models have tutorials, forums, and troubleshooting guides. This external support often matters more than manufacturer documentation.

For a beginner, success should feel achievable. Learning should come from exploration, not constant repair. Simplicity supports momentum.

Material Compatibility

Material compatibility influences what a beginner can realistically print. Many first-time users underestimate this factor. They focus on machine features instead of material behavior.

PLA dominates beginner use for good reason. It prints easily and behaves predictably. Machines that handle PLA well already cover many needs.

Support for additional materials expands options gradually. Heated beds enable ABS or PETG. Enclosures improve consistency. These features matter later, not immediately.

A beginner 3D printer should grow with the user. It should handle basic materials reliably and allow expansion without replacement.

3D Printer Price Range and Operating Costs

Price discussions often stop at the purchase stage. In practice, ownership costs extend well beyond the initial transaction. Understanding this prevents unrealistic expectations.

A 3D printer price reflects hardware capability, build quality, and support. It does not reflect long-term expense alone. Materials, maintenance, and time also matter.

Entry-Level vs Professional Models

Entry-level machines focus on accessibility. They aim to reduce barriers. Print quality may be lower, but learning value remains high.

Professional models emphasize precision and durability. They justify higher cost through consistency and performance. These machines suit environments where time equals money.

The difference is not only output quality. Professional systems reduce downtime. They require less adjustment. This reliability matters in production contexts.

Beginners rarely need professional-grade equipment. The learning curve benefits more from hands-on adjustment than automation. Experience builds judgment.

Material and Maintenance Costs

Materials represent a recurring expense. Filament costs vary by type and quality. Cheaper options save money but may cause failures.

Maintenance costs appear gradually. Nozzles wear down. Beds need cleaning or replacement. Belts loosen. These expenses remain manageable but unavoidable.

Electricity consumption is modest but continuous. Long prints add up over time. Ventilation may also require attention, depending on materials used.

Operating costs remain reasonable for most users. They become significant only with heavy use. Planning ahead avoids surprise expenses.

Maintenance and Basic Troubleshooting

Ownership includes responsibility. Machines perform best when cared for consistently. Ignoring maintenance shortens lifespan and increases failure rates.

Many common issues appear unrelated at first. In reality, they trace back to simple neglect. Routine attention prevents most problems.

Routine Maintenance

Basic cleaning makes a noticeable difference. Dust and debris affect motion systems. Residue affects extrusion. Small efforts preserve consistency.

Bed leveling requires regular checks. Thermal expansion and movement cause drift. A level bed supports adhesion and accuracy.

Lubrication of moving parts reduces wear. Smooth motion improves surface finish. Noise often signals friction or resistance.

Firmware updates also matter. Improvements often address stability issues. Staying current reduces unexplained behavior.

Common Problems and Fixes

Some issues appear repeatedly among beginners. Poor adhesion often results from incorrect bed distance or contamination. Cleaning and leveling usually solve it.

Under-extrusion signals material flow issues. Clogs, worn gears, or incorrect temperature are common causes. Inspection reveals the source.

Layer shifting often points to mechanical looseness. Belts or pulleys need tightening. Ignoring early signs worsens results.

Understanding common 3D printing problems reduces anxiety. Most failures are fixable. Experience turns frustration into routine adjustment.

Consistent maintenance turns troubleshooting into prevention. A well-maintained machine behaves predictably. Reliability builds trust.

Is a 3D Printer Right for You?

Before purchasing, it helps to pause. Not every problem requires this technology. Not every user enjoys the process.

A 3D printer rewards curiosity and patience. It suits people who enjoy experimentation. Learning comes through iteration rather than instant results.

Those seeking finished products without involvement may feel disappointed. Printing requires setup, adjustment, and observation. It is an active process.

For others, the appeal lies in control. Design decisions translate directly into outcomes. The machine becomes an extension of creative intent.

According to expert interviews in a 3D printing industry study, additive manufacturing has significant disruptive potential, particularly in medical and engineered product applications. This impact comes from flexibility rather than speed.

The same principle applies at a personal level. Value emerges when the technology matches expectations. For the right user, a 3D printer becomes more than a tool. It becomes a way of thinking about making things.

FAQs About 3D Printers

Is it worth it to own a 3D printer?

It is worth it if you enjoy making, testing, and adjusting ideas. The value comes from control and iteration, not instant results.

How much does a 3D printer cost?

Entry-level machines are affordable, while professional models cost significantly more. Ongoing expenses include materials and basic maintenance.

What is the lifespan of a 3D printer?

With regular care, a machine can last many years. Wear parts need replacement, but the core system remains usable.

Is 3D printing difficult for beginners?

The basics are approachable. Early challenges exist, but progress comes quickly with practice and patience.

What am I not allowed to 3D print?

Laws vary by region. Restricted items often include weapons, regulated parts, and copyrighted designs. Always check local regulations.